Your gateway to endless inspiration

Planets - Blog Posts

What are three things you would want everyone to know about your work?

Are there any parts of the Earth still left unexplored?

Is Earth your favorite planet? Why or why not?

Up for some virtual cloud watching? ☁️

What do you see in Jupiter's hazy atmosphere?

Our NASA JunoCam mission captured this look at the planet’s thunderous northern region during the spacecraft’s close approach to the planet on Feb. 17, 2020.

Some notable features in this view are the long, thin bands that run through the center of the image from top to bottom. Juno has observed these long streaks since its first close pass by Jupiter in 2016.

Image Credits: Image data: NASA / JPL / SwRI / MSSS Image Processing: Citizen Scientist Eichstädt

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Allow us to reintroduce someone ... the name’s Perseverance.

With this new name, our Mars 2020 rover has now come to life! Chosen by middle school student Alex Mather, Perseverance helps to remind ourselves that no matter what obstacles we face, whether it's on the way to reaching our goals or on the way to Mars, we will push through. In Alex’s own words,

“We are a species of explorers, and we will meet many setbacks on the way to Mars. However, we can persevere. We, not as a nation but as humans, will not give up. The human race will always persevere into the future.”

Welcome to the family. ❤️

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

#TBT to 1989 when Voyager 2 spotted Uranus looking like a seemingly perfect robin’s egg. 💙 When our Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by it in this image, one pole was pointing directly at the Sun. This means that no matter how much it spins, one half is completely in the sun at all times, and the other half is in total darkness.. Far-flung, Uranus – an ice giant of our solar system – is as mysterious as it is distant. Soon after its launch in 2021, our James Webb Space Telescope will change that by unlocking secrets of its atmosphere. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Exploring Hell... up for the challenge?

Venus is an EXTREME world, and we’re calling on YOU to help us explore it! NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory is running a public challenge to develop an obstacle avoidance sensor for a possible future Venus rover.

With a surface temperature in excess of 840 degrees Fahrenheit and a surface pressure 92 times that of Earth, Venus can turn lead into a puddle and crush a nuclear-powered submarine with ease. While many missions have visited our sister planet, only about a dozen have made contact with the surface of Venus before succumbing to the oppressive heat and pressure after just about more than an hour.

The “Exploring Hell: Avoiding Obstacles on a Clockwork Rover” challenge is seeking the public’s designs for a sensor that could be incorporated into the design concept. The winning sensor could be the primary mechanism by which the rover detects and navigates around obstructions.

Award: 1st Place - $15,000; 2nd Place - $10,000; 3rd Place - $5,000

Open Date: February 18, 2020 ––––––––– Close Date: May 29, 2020

In Roman mythology, the god Jupiter drew a veil of clouds around himself to hide his mischief. It was only Jupiter's wife, the goddess Juno, who could peer through the clouds and reveal Jupiter's true nature. Our @NASAJuno spacecraft is looking beneath the clouds of the massive gas giant, not seeking signs of misbehavior, but helping us to understand the planet's structure and history... Now, @NASAJuno just published its first findings on the amount of water in the gas giant’s atmosphere. The Juno results estimate that at the equator, water makes up about 0.25% of the molecules in Jupiter's atmosphere — almost three times that of the Sun. An accurate total estimate of this water is critical to solving the mystery of how our solar system formed.

The JunoCam imager aboard Juno captured this image of Jupiter's southern equatorial region on Sept. 1, 2017. The bottom image is oriented so Jupiter's poles (not visible) run left-to-right of frame.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill

INCOMING! Roving scientist to arrive on Mars.

Save the date! One year from today, Feb. 18, 2021, our next rover is set to land on Mars. Get to know #Mars2020 now! Click here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

It was a dark and stormy flyby...

Our @NASAJuno spacecraft's JunoCam captured images of the chaotic, stormy northern hemisphere of Jupiter during its 24th close pass of the giant planet on Dec. 26, 2019. Using data from the flyby, citizen scientist Kevin M. Gill created this color-enhanced image. At the time, the spacecraft was about 14,600 miles (23,500 kilometers) from the tops of Jupiter’s clouds, at a latitude of about 69 degrees north.

Image Credit: Image data: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS

Image processing by Kevin M. Gill, © CC BY

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Are We Alone? How NASA Is Trying to Answer This Question.

One of the greatest mysteries that life on Earth holds is, “Are we alone?”

At NASA, we are working hard to answer this question. We’re scouring the universe, hunting down planets that could potentially support life. Thanks to ground-based and space-based telescopes, including Kepler and TESS, we’ve found more than 4,000 planets outside our solar system, which are called exoplanets. Our search for new planets is ongoing — but we’re also trying to identify which of the 4,000 already discovered could be habitable.

Unfortunately, we can’t see any of these planets up close. The closest exoplanet to our solar system orbits the closest star to Earth, Proxima Centauri, which is just over 4 light years away. With today’s technology, it would take a spacecraft 75,000 years to reach this planet, known as Proxima Centauri b.

How do we investigate a planet that we can’t see in detail and can’t get to? How do we figure out if it could support life?

This is where computer models come into play. First we take the information that we DO know about a far-off planet: its size, mass and distance from its star. Scientists can infer these things by watching the light from a star dip as a planet crosses in front of it, or by measuring the gravitational tugging on a star as a planet circles it.

We put these scant physical details into equations that comprise up to a million lines of computer code. The code instructs our Discover supercomputer to use our rules of nature to simulate global climate systems. Discover is made of thousands of computers packed in racks the size of vending machines that hum in a deafening chorus of data crunching. Day and night, they spit out 7 quadrillion calculations per second — and from those calculations, we paint a picture of an alien world.

While modeling work can’t tell us if any exoplanet is habitable or not, it can tell us whether a planet is in the range of candidates to follow up with more intensive observations.

One major goal of simulating climates is to identify the most promising planets to turn to with future technology, like the James Webb Space Telescope, so that scientists can use limited and expensive telescope time most efficiently.

Additionally, these simulations are helping scientists create a catalog of potential chemical signatures that they might detect in the atmospheres of distant worlds. Having such a database to draw from will help them quickly determine the type of planet they’re looking at and decide whether to keep observing or turn their telescopes elsewhere.

Learn more about exoplanet exploration, here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Celestial Mechanics Around the Solar System During December 2019

The dance of planets, moons and spacecraft around the solar system creates a host of rare alignments in late December 2019. Here's what's coming up.

Dec. 21: Winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere

Dec. 21 is the 2019 winter solstice for the Northern Hemisphere. A solstice marks the point at which Earth's tilt is at the greatest angle to the plane of its orbit, also the point where half of the planet is receiving the longest stretch of daylight and the other the least. There are two solstices a year, in June and December: the summer and winter solstices, respectively, in the Northern Hemisphere.

The winter solstice is the longest night of the year, when that hemisphere of Earth is tilted farthest from the Sun and receives the fewest hours of sunlight in a given year. Starting Dec. 21, the days will get progressively longer until the June solstice for those in the Northern Hemisphere, and vice versa for the Southern Hemisphere.

Dec. 26: Annular solar eclipse visible in Asia

On Dec. 26, an annular solar eclipse will be visible in parts of Asia. During an annular eclipse, the Moon's apparent size is too small to completely cover the face of the Sun, creating a "ring of fire" around the Moon's edge during the eclipse.

Credit: Dale Cruikshank

Solar eclipses happen when the Moon lines up just right with the Sun and Earth. Though the Moon orbits Earth about once a month, the tilt in its orbit means that it's relatively rare for the Moon to pass right in line between the Sun and Earth — and those are the conditions that create an eclipse. Depending on the alignment, the Moon can create a partial, total or annular solar eclipse.

On Dec. 26, the Moon will be near perigee, the point in its orbit when it's farthest from Earth. That means its apparent size from Earth is just a bit smaller — and that difference means that it won't completely cover the Sun during the Dec. 26 eclipse. Instead, a ring of the bright solar surface will be visible around the Moon during the point of greatest eclipse. This is called an annular eclipse.

It is never safe to look directly at an annular solar eclipse, because part of the Sun is always visible. If you're in the path of the annular eclipse, be sure to use solar viewing glasses (not sunglasses) or another safe viewing method to watch the eclipse.

Dec. 26: Parker Solar Probe flies by Venus

After the eclipse, more than 100 million miles away from Earth, Parker Solar Probe will pull off a celestial maneuver of its own. On Dec. 26, the spacecraft will perform the second Venus gravity assist of the mission to tighten its orbit around the Sun.

During the seven gravity assists throughout the mission, Parker Solar Probe takes advantage of Venus's gravity to slow down just the right amount at just the right time. Losing some of its energy allows the spacecraft to be drawn closer by the Sun's gravity: It will fly by the Sun's surface at just 11.6 million miles during its next solar flyby on Jan. 29, 2020. During this flyby, Parker Solar Probe will break its own record for closest-ever spacecraft to the Sun and will gather new data to build on the science already being shared from the mission.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

SPACE: A Global Frontier

Space is a global frontier. That’s why we partner with nations all around the world to further the advancement of science and to push the boundaries of human exploration. With international collaboration, we have sent space telescopes to observe distant galaxies, established a sustainable, orbiting laboratory 254 miles above our planet’s surface and more! As we look forward to the next giant leaps in space exploration with our Artemis lunar exploration program, we will continue to go forth with international partnerships!

Teamwork makes the dream work. Here are a few of our notable collaborations:

Artemis Program

Our Artemis lunar exploration program will send the first woman and the next man to the Moon by 2024. Using innovative technologies and international partnerships, we will explore more of the lunar surface than ever before and establish sustainable missions by 2028.

During these missions, the Orion spacecraft will serve as the exploration vehicle that will carry the crew to space, provide emergency abort capability and provide safe re-entry from deep space return velocities. The European Service Module, provided by the European Space Agency, will serve as the spacecraft’s powerhouse and supply it with electricity, propulsion, thermal control, air and water in space.

The Gateway, a small spaceship that will orbit the Moon, will be a home base for astronauts to maintain frequent and sustainable crewed missions to the lunar surface. With the help of a coalition of nations, this new spaceship will be assembled in space and built within the next decade.

Gateway already has far-reaching international support, with 14 space agencies agreeing on its importance in expanding humanity's presence on the Moon, Mars and deeper into the solar system.

International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is one of the most ambitious international collaborations ever attempted. Launched in 1998 and involving the U.S., Russia, Canada, Japan and the participating countries of the European Space Agency — the ISS has been the epitome of global cooperation for the benefit of humankind. The largest space station ever constructed, the orbital laboratory continues to bring together international flight crews, globally distributed launches, operations, training, engineering and the world’s scientific research community.

Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope, one of our greatest windows into worlds light-years away, was built with contributions from the European Space Agency (ESA).

ESA provided the original Faint Object Camera and solar panels, and continues to provide science operations support for the telescope.

Deep Space Network

The Deep Space Network (DSN) is an international array of giant radio antennas that span the world, with stations in the United States, Australia and Spain. The three facilities are equidistant approximately one-third of the way around the world from one another – to permit constant communication with spacecraft as our planet rotates. The network supports interplanetary spacecraft missions and a few that orbit Earth. It also provides radar and radio astronomy observations that improve our understanding of the solar system and the larger universe!

Mars Missions

Information gathered today by robots on Mars will help get humans to the Red Planet in the not-too-distant future. Many of our Martian rovers – both past, present and future – are the products of a coalition of science teams distributed around the globe. Here are a few notable ones:

Curiosity Mars Rover

France: ChemCam, the rover’s laser instrument that can analyze rocks from more than 20 feet away

Russia: DAN, which looks for subsurface water and water locked in minerals

Spain: REMS, the rover’s weather station

InSight Mars Lander

France with contributions from Switzerland: SEIS, the first seismometer on the surface of another planet

Germany: HP3, the heatflow probe that will help us understand the interior structure of Mars

Spain: APSS, the lander’s weather station

Mars 2020 Rover

Norway: RIMFAX, a ground-penetrating radar

France: SuperCam, the laser instrument for remote science

Spain: MEDA, the rover’s weather station

Space-Analog Astronaut Training

We partner with space agencies around the globe on space-analog missions. Analog missions are field tests in locations that have physical similarities to the extreme space environments. They take astronauts to space-like environments to prepare as international teams for near-term and future exploration to asteroids, Mars and the Moon.

The European Space Agency hosts the Cooperative Adventure for Valuing and Exercising human behavior and performance Skills (CAVES) mission. The two week training prepares multicultural teams of astronauts to work safely and effectively in an environment where safety is critical. The mission is designed to foster skills such as communication, problem solving, decision-making and team dynamics.

We host our own analog mission, underwater! The NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO) project sends international teams of astronauts, engineers and scientists to live in the world’s only undersea research station, Aquarius, for up to three weeks. Here, “aquanauts” as we call them, simulate living on a spacecraft and test spacewalk techniques for future space missions in hostile environments.

International Astronautical Congress

So, whether we’re collaborating as a science team around the globe, or shoulder-to-shoulder on a spacewalk, we are committed to working together with international partners for the benefit of all humanity!

If you’re interested in learning more about how the global space industry works together, check out our coverage of the 70th International Astronautical Congress (IAC) happening this week in Washington, D.C. IAC is a yearly gathering in which all space players meet to talk about the advancements and progress in exploration.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

The Science Goals of the James Webb Space Telescope

Our James Webb Space Telescope is an epic mission that will give us a window into the early universe, allowing us to see the time period during which the first stars and galaxies formed. Webb will not only change what we know, but also how we think about the night sky and our place in the cosmos. Want to learn more? Join two of our scientists as they talk about what the James Webb Telescope is, why it is being built and what it will help us learn about the universe…

First, meet Dr. Amber Straughn. She grew up in a small farming town in Arkansas, where her fascination with astronomy began under beautifully dark, rural skies. After finishing a PhD in Physics, she came to NASA Goddard to study galaxies using data from our Hubble Space Telescope. In addition to research, Amber's role with the Webb project’s science team involves working with Communications and Outreach activities. She is looking forward to using data from Webb in her research on galaxy formation and evolution.

We also talked with Dr. John Mather, the Senior Project Scientist for Webb, who leads our science team. He won a Nobel Prize in 2006 for confirming the Big Bang theory with extreme precision via a mission called the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) mission. John was the Principal Investigator (PI) of the Far IR Absolute Spectrophotometer (FIRAS) instrument on COBE. He’s an expert on cosmology, and infrared astronomy and instrumentation.

Now, let’s get to the science of Webb!

Dr. Amber Straughn: The James Webb Space Telescope at its core is designed to answer some of the biggest questions we have in astronomy today. And these are questions that go beyond just being science questions; they are questions that really get to the heart of who we are as human beings; questions like where do we come from? How did we get here? And, of course, the big one – are we alone?

To answer the biggest questions in astronomy today we really need a very big telescope. And the James Webb Space Telescope is the biggest telescope we’ve ever attempted to send into space. It sets us up with some really big engineering challenges.

Dr. John Mather: One of the wonderful challenges about astronomy is that we have to imagine something so we can go look for it. But nature has a way of being even more creative than we are, so we have always been surprised by what we see in the sky. That’s why building a telescope has always been interesting. Every time we build a better one, we see something we never imagined was out there. That’s been going on for centuries. This is the next step in that great series, of bigger and better and more powerful telescopes that surely will surprise us in some way that I can’t tell you.

It has never been done before, building a big telescope that will unfold in space. We knew we needed something that was bigger than the rocket to achieve the scientific discoveries that we wanted to make. We had to invent a new way to make the mirrors, a way to focus it out in outer space, several new kinds of infrared detectors, and we had to invent the big unfolding umbrella we call the sunshield.

Amber: One of Webb’s goals is to detect the very first stars and galaxies that were born in the very early universe. This is a part of the universe that we haven’t seen at all yet. We don’t know what’s there, so the telescope in a sense is going to open up this brand-new part of the universe, the part of the universe that got everything started.

John: The first stars and galaxies are really the big mystery for us. We don’t know how that happened. We don’t know when it happened. We don’t know what those stars were like. We have a pretty good idea that they were very much larger than the sun and that they would burn out in a tremendous burst of glory in just a few million years.

Amber: We also want to watch how galaxies grow and change over time. We have questions like how galaxies merge, how black holes form and how gas inflows and outflows affect galaxy evolution. But we’re really missing a key piece of the puzzle, which is how galaxies got their start.

John: Astronomy is one of the most observationally based sciences we’ve ever had. Everything we know about the sky has been a surprise. The ancients knew about the stars, but they didn’t know they were far away. They didn’t know they were like the Sun. Eventually we found that our own galaxy is one of hundreds of billions of galaxies and that the Universe is actually very old, but not infinitely old. So that was a big surprise too. Einstein thought, of course the Universe must have an infinite age, without a starting point. Well, he was wrong! Our intuition has just been wrong almost all the time. We’re pretty confident that we don’t know what we’re going to find.

Amber: As an astronomer one of the most exciting things about working on a telescope like this is the prospect of what it will tell us that we haven’t even thought of yet. We have all these really detailed science questions that we’ll ask, that we know to ask, and that we’ll answer. And in a sense that is what science is all about… in answering the questions we come up with more questions. There’s this almost infinite supply of questions, of things that we have to learn. So that’s why we build telescopes to get to this fundamental part of who we are as human beings. We’re explorers, and we want to learn about what our Universe is like.

Webb will be the world's premier space science observatory. It will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe – including our place in it. Webb is an international project we’re leading with our partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.

To learn more about our James Webb Space Telescope, visit the website, or follow the mission on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

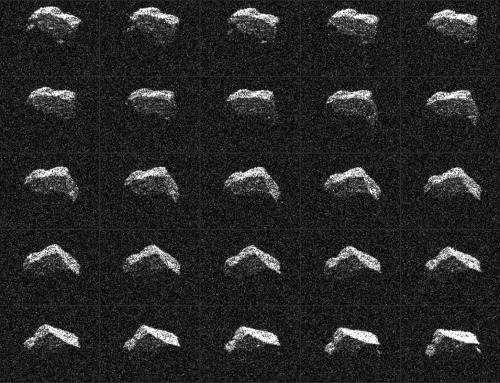

Protecting our Home Planet 🌎

Did you ever wonder how we spots asteroids that may be getting too close to Earth for comfort? Wonder no more. Our Planetary Defense Coordination Office does just that. Thanks to a variety of ground and space based telescopes, we’re able to detect potentially hazardous objects so we can prepare for the unlikely threat against our planet.

What is a near-Earth object?

Near-Earth objects (NEOs) are asteroids and comets that orbit the Sun, but their orbits bring them into Earth’s neighborhood – within 30 million miles of Earth’s orbit.

These objects are relatively unchanged remnant debris from the solar system’s formation some 4.6 billion years ago. Most of the rocky asteroids originally formed in the warmer inner solar system between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, while comets, composed mostly of water ice with embedded dust particles, formed in the cold outer solar system.

Who searches for near-Earth objects?

Our Near-Earth Object (NEO) Observations Program finds, tracks and monitors near-Earth asteroids and comets. Astronomers supported by the program use telescopes to follow up the discoveries to make additional measurements, as do many observatories all over the world. The Center for Near-Earth Object Studies, based at our Jet Propulsion Laboratory, also uses these data to calculate high-precision orbits for all known near-Earth objects and predict future close approaches by them to Earth, as well as the potential for any future impacts.

How do we calculate the orbit of a near-Earth object?

Scientists determine the orbit of an asteroid by comparing measurements of its position as it moves across the sky to the predictions of a computer model of its orbit around the Sun. The more observations that are used and the longer the period over which those observations are made, the more accurate the calculated orbit and the predictions that can be made from it.

How many near-Earth objects have been discovered so far?

At the start of 2019, the number of discovered NEOs totaled more than 19,000, and it has since surpassed 20,000. An average of 30 new discoveries are added each week. More than 95 percent of these objects were discovered by NASA-funded surveys since 1998, when we initially established its NEO Observations Program and began tracking and cataloguing them.

Currently the risk of an asteroid striking Earth is exceedingly low, but we are constantly monitoring our cosmic neighborhood. Have more questions? Visit our Planetary Defense page to explore how we keep track of near-Earth objects.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Got a question about black holes? Let’s get to the bottom of these odd phenomena. Ask our black hole expert anything!

Black holes are mystifying yet terrifying cosmic phenomena. Unfortunately, people have a lot of ideas about them that are more science fiction than science. Don’t worry! Our black hole expert, Jeremy Schnittman, will be answering your your questions in an Answer Time session on Wednesday, October 2 from 3pm - 4 pm ET here on NASA’s Tumblr! Make sure to ask your question now by visiting http://nasa.tumblr.com/ask!

Jeremy joined the Astrophysics Science Division at our Goddard Space Flight Center in 2010 following postdoctoral fellowships at the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins University. His research interests include theoretical and computational modeling of black hole accretion flows, X-ray polarimetry, black hole binaries, gravitational wave sources, gravitational microlensing, dark matter annihilation, planetary dynamics, resonance dynamics and exoplanet atmospheres. He has been described as a "general-purpose astrophysics theorist," which he regards as quite a compliment.

Fun Fact: The computer code Jeremy used to make the black hole animations we featured last week is called "Pandurata," after a species of black orchid from Sumatra. The name pays homage to the laser fusion lab at the University of Rochester where Jeremy worked as a high school student and wrote his first computer code, "Buttercup." All the simulation codes at the lab are named after flowers.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

We are swooningggg over this NEW Saturn image.

Saturn is so beautiful that astronomers cannot resist using the Hubble Space Telescope to take yearly snapshots of the ringed world when it is at its closest distance to Earth. 😍

These images, however, are more than just beauty shots. They reveal exquisite details of the planet as a part of the Outer Planets Atmospheres Legacy project to help scientists understand the atmospheric dynamics of our solar system's gas giants.

This year's Hubble offering, for example, shows that a large storm visible in the 2018 Hubble image in the north polar region has vanished. Also, the mysterious six-sided pattern – called the "hexagon" – still exists on the north pole. Caused by a high-speed jet stream, the hexagon was first discovered in 1981 by our Voyager 1 spacecraft.

Saturn's signature rings are still as stunning as ever. The image reveals that the ring system is tilted toward Earth, giving viewers a magnificent look at the bright, icy structure.

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, A. Simon (GSFC), M.H. Wong (University of California, Berkeley) and the OPAL Team

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Is the earth really as beautiful as they say from space?

How Do We Learn About a Planet’s Atmosphere?

The first confirmation of a planet orbiting a star outside our solar system happened in 1995. We now know that these worlds – also known as exoplanets – are abundant. So far, we’ve confirmed more than 4000. Even though these planets are far, far away, we can still study them using ground-based and space-based telescopes.

Our upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will study the atmospheres of the worlds in our solar system and those of exoplanets far beyond. Could any of these places support life? What Webb finds out about the chemical elements in these exoplanet atmospheres might help us learn the answer.

How do we know what’s in the atmosphere of an exoplanet?

Most known exoplanets have been discovered because they partially block the light of their suns. This celestial photo-bombing is called a transit.

During a transit, some of the star's light travels through the planet's atmosphere and gets absorbed.

The light that survives carries information about the planet across light-years of space, where it reaches our telescopes.

(However, the planet is VERY small relative to the star, and VERY far away, so it is still very difficult to detect, which is why we need a BIG telescope to be sure to capture this tiny bit of light.)

So how do we use a telescope to read light?

Stars emit light at many wavelengths. Like a prism making a rainbow, we can separate light into its separate wavelengths. This is called a spectrum. Learn more about how telescopes break down light here.

Visible light appears to our eyes as the colors of the rainbow, but beyond visible light there are many wavelengths we cannot see.

Now back to the transiting planet...

As light is traveling through the planet's atmosphere, some wavelengths get absorbed.

Which wavelengths get absorbed depends on which molecules are in the planet's atmosphere. For example, carbon monoxide molecules will capture different wavelengths than water vapor molecules.

So, when we look at that planet in front of the star, some of the wavelengths of the starlight will be missing, depending on which molecules are in the atmosphere of the planet.

Learning about the atmospheres of other worlds is how we identify those that could potentially support life...

...bringing us another step closer to answering one of humanity's oldest questions: Are we alone?

Watch the full video where this method of hunting for distant planets is explained:

To learn more about NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, visit the website, or follow the mission on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Text and graphics credit Space Telescope Science Institute

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

How Do Space Telescopes Break Down Light?

Space telescopes like Hubble and our upcoming James Webb Space Telescope use light not only to create images, but can also break light down into individual colors (or wavelengths). Studying light this way can give us a lot of detail about the object that emitted that light. For example, studying the components of the light from exoplanets can tell us about its atmosphere’s color, chemical makeup, and temperature. How does this work?

Remember the primary colors you learned about in elementary school?

Those colors are known as the pigment or subtractive colors. Every other color is some combination of the primary colors: red, yellow, and blue.

Light also has its own primary colors, and they work in a similar way. These colors are known as additive or light colors.

TVs make use of light’s colors to create the pictures we see. Each pixel of a TV screen contains some amount of red, green and blue light. The amount of each light determines the overall color of the pixel. So, each color on the TV comes from a combination of the primary colors of light: red, green and blue.

Space telescope images of celestial objects are also a combination of the colors of light.

Every pixel that is collected can be broken down into its base colors. To learn even more, astronomers break the red, green and blue light down into even smaller sections called wavelengths.

This breakdown is called a spectrum.

With the right technology, every pixel of light can also be measured as a spectrum.

Images show us the big picture, while a spectrum reveals finer details. Astronomers use spectra to learn things like what molecules are in planet atmospheres and distant galaxies.

An Integral Field Unit, or IFU, is a special tool on the James Webb Space Telescope that captures images and spectra at the same time.

The IFU creates a unique spectrum for each pixel of the image the telescope is capturing, providing scientists with an enormous amount of valuable, detailed data. So, with an IFU we can get an image, many spectra and a better understanding of our universe.

Watch the full video where this method of learning about planetary atmospheres is explained:

The James Webb Space Telescope is our upcoming infrared space observatory, which will launch in 2021. It will spy the first galaxies that formed in the universe and shed light on how galaxies evolve, how stars and planetary systems are born and tell us about potentially habitable planets around other stars.

To learn more about NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, visit the website, or follow the mission on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Text and graphics credit: Space Telescope Science Institute

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

TESS’s first-year of planet-hunting was out of this world

Have you ever looked up at the night sky and wondered ... what other kinds of planets are out there? Our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) just spent its first year bringing us a step closer to exploring the planets around the nearest and brightest stars in the southern sky and is now doing the same in the north.

TESS has been looking for dips in the brightness of stars that could be a sign of something we call “transits.” A transit happens when a planet passes between its star and us. It’s like when a bug flies in front of a light bulb. You may not notice the tiny drop in brightness when the bug blocks some of the light from reaching your eyes, but a sensitive camera could. The cameras on TESS are designed to detect those tiny drops in starlight caused by a transiting planet many light-years away.

In the last year TESS has found 24 planets and more than 900 new candidate planets. And TESS is only halfway through its goal of mapping over three-fourths of our skies, which means there’s plenty more to discover!

TESS has been looking for planets around the closest, brightest stars because they will be the best planets to explore more thoroughly with future missions. We can even see a few of these stars with our own eyes, which means we’ve been looking at these planets for millions of years and didn’t even know it.

We spent thousands of years staring at our closest neighbor, the Moon, and asking questions: What is it like? Could we live there? What is it made of (perhaps cheese?). Of course, now we can travel to the Moon and explore it ourselves (turns out, not made of cheese).

But for the worlds TESS is discovering, the commute to answer those questions would be killer. It took 35 years for Voyager 1 to cross into interstellar space (the region between stars), and it’s zipping along at over 38,000 mph! At that rate it would take more than a half-a-million years to reach the nearest stars and planets that TESS is discovering.

While exploring these distant worlds in person isn’t an option, we have other ways of learning what they are like. TESS can tell us where a planet is, its size and its overall temperature, but observatories on the ground and in space like our upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will be able to learn even more — like whether or not a planet has an atmosphere and what it’s made of.

Here are a few of the worlds that our planet hunter discovered in the last year.

Earth-Sized Planet

The first Earth-sized planet discovered by TESS is about 90% the size of our home planet and orbits a star 53 light-years away. The planet is called HD 21749 c (what a mouthful!) and is actually the second planet TESS has discovered orbiting that star, which you can see in the southern constellation Reticulum.

The planet may be Earth-sized, but it would not be a pleasant place to live. It’s very close to its star and could have a surface temperature of 800 degrees Fahrenheit, which would be like sitting inside a commercial pizza oven.

Water World?

The other planet discovered in that star system, HD 21749 b, is about three times Earth’s size and orbits the star every 36 days. It has the longest orbit of any planet within 100 light-years of our solar system detected with TESS so far.

The planet is denser than Neptune, but isn’t made of rock. Scientists think it might be a water planet or have a totally new type of atmosphere. But because the planet isn’t ideal for follow-up study, for now we can only theorize what the planet is actually like. Could it be made of pudding? Maybe … but probably not.

Magma World

One of the first planets TESS discovered, called LHS 3844 b, is roughly Earth’s size, but is so close to its star that it orbits in just 11 hours. For reference, Mercury, which is more than two and a half times closer to the Sun than we are, completes an orbit in just under three months.

Because the planet is so close to its star, the day side of the planet might get so hot that pools and oceans of magma form on its rocky surface, which would make for a rather unpleasant day at the beach.

TESS’s Smallest Planet

The smallest planet TESS has discovered, called L 98-59 b, is between the size of Earth and Mars and orbits its star in a little over two days. Its star also hosts two other TESS-discovered worlds.

Because the planet lies so close to its star, it gets 22 times the radiation we get here on Earth. Yikes! It is also not located in its star’s habitable zone, which means there probably isn’t any liquid water on the surface. Those two factors make it an unlikely place to find life, but scientists believe it will be a good candidate for follow-up studies by other telescopes.

Other Data

While TESS’s team is hunting for planets around close, bright stars, it’s also collecting information on all sorts of other things. From transits around dimmer, farther stars to other objects in our solar system and events outside our galaxy, data from TESS can help astronomers learn a lot more about the universe. Comets and black holes and supernovae, oh my!

Interested in joining the hunt? TESS’s data are released online, so citizen scientists around the world can help us discover new worlds and better understand our universe.

Stay tuned for TESS’s next year of science as it monitors the stars that more than 6.5 billion of us in the northern hemisphere see every night.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

6 Things You Didn’t Know About Our ‘First’ Space Flight Center

When NASA began operations on Oct. 1, 1958, we consisted mainly of the four laboratories of our predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). Hot on the heels of NASA’s first day of business, we opened the Goddard Space Flight Center. Chartered May 1, 1959, and located in Greenbelt, Maryland, Goddard is home to one of the largest groups of scientists and engineers in the world. These people are building, testing and experimenting their way toward answering some of the universe’s most intriguing questions.

To celebrate 60 years of exploring, here are six ways Goddard shoots for the stars.

For the last 60 years, we’ve kept a close eye on our home planet, watching its atmosphere, lands and ocean.

Goddard instruments were crucial in tracking the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica as it grew and eventually began to show signs of healing. Satellites and field campaigns track the changing height and extent of ice around the globe. Precipitation missions give us a global, near-real-time look at rain and snow everywhere on Earth. Researchers keep a record of the planet’s temperature, and Goddard supercomputer models consider how Earth will change with rising temperatures. From satellites in Earth’s orbit to field campaigns in the air and on the ground, Goddard is helping us understand our planet.

We seek to answer the big questions about our universe: Are we alone? How does the universe work? How did we get here?

We’re piecing together the story of our cosmos, from now all the way back to its start 13.7 billion years ago. Goddard missions have contributed to our understanding of the big bang and have shown us nurseries where stars are born and what happens when galaxies collide. Our ongoing census of planets far beyond our own solar system (several thousand known and counting!) is helping us hone in on which ones might be potentially habitable.

We study our dynamic Sun.

Our Sun is an active star, with occasional storms and a constant outflow of particles, radiation and magnetic fields that fill the solar system out far past the orbit of Neptune. Goddard scientists study the Sun and its activity with a host of satellites to understand how our star affects Earth, planets throughout the solar system and the nature of the very space our astronauts travel through.

We explore the planets, moons and small objects in the solar system and beyond.

Goddard instruments (well over 100 in total!) have visited every planet in the solar system and continue on to new frontiers. What we’ve learned about the history of our solar system helps us piece together the mysteries of life: How did life in our solar system form and evolve? Can we find life elsewhere?

Over 60 years, our communications networks have enabled hundreds of NASA spacecraft to “phone home.”

Today, Goddard communications networks bring down 98 percent of our spacecraft data – nearly 30 terabytes per day! This includes not only science data, but also key information related to spacecraft operations and astronaut health. Goddard is also leading the way in creating cutting-edge solutions like laser communications that will enable exploration – faster, better, safer – for generations to come. Pew pew!

Exploring the unknown often means we must create new ways of exploring, new ways of knowing what we’re “seeing.”

Goddard’s technologists and engineers must often invent tools, mechanisms and sensors to return information about our universe that we may not have even known to look for when the center was first commissioned.

Behind every discovery is an amazing team of people, pushing the boundaries of humanity’s knowledge. Here’s to the ones who ask questions, find answers and ask questions some more!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

How Big is Our Galaxy, the Milky Way?

When we talk about the enormity of the cosmos, it’s easy to toss out big numbers – but far harder to wrap our minds around just how large, how far and how numerous celestial bodies like exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – really are.

So. How big is our Milky Way Galaxy?

We use light-time to measure the vast distances of space.

It’s the distance that light travels in a specific period of time. Also: LIGHT IS FAST, nothing travels faster than light.

How far can light travel in one second? 186,000 miles. It might look even faster in metric: 300,000 kilometers in one second. See? FAST.

How far can light travel in one minute? 11,160,000 miles. We’re moving now! Light could go around the Earth a bit more than 448 times in one minute.

Speaking of Earth, how long does it take light from the Sun to reach our planet? 8.3 minutes. (It takes 43.2 minutes for sunlight to reach Jupiter, about 484 million miles away.) Light is fast, but the distances are VAST.

In an hour, light can travel 671 million miles. We’re still light-years from the nearest exoplanet, by the way. Proxima Centauri b is 4.2 light-years away. So… how far is a light-year? 5.8 TRILLION MILES.

A trip at light speed to the very edge of our solar system – the farthest reaches of the Oort Cloud, a collection of dormant comets way, WAY out there – would take about 1.87 years.

Our galaxy contains 100 to 400 billion stars and is about 100,000 light-years across!

One of the most distant exoplanets known to us in the Milky Way is Kepler-443b. Traveling at light speed, it would take 3,000 years to get there. Or 28 billion years, going 60 mph. So, you know, far.

SPACE IS BIG.

Read more here: go.nasa.gov/2FTyhgH

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Mars in a Box: How a Metal Chamber on Earth Helps us do Experiments on Mars

Inside this metal box, it’s punishingly cold. The air is unbreathable. The pressure is so low, you’d inflate like a balloon. This metal chamber is essentially Mars in a box — or a near-perfect replica of the Martian environment. This box allows scientists to practice chemistry experiments on Earth before programming NASA’s Curiosity rover to carry them out on Mars. In some cases, scientists use this chamber to duplicate experiments from Mars to better understand the results. This is what’s happening today.

The ladder is set so an engineer can climb to the top of the chamber to drop in a pinch of lab-made Martian rock. A team of scientists is trying to duplicate one of Curiosity’s first experiments to settle some open questions about the origin of certain organic compounds the rover found in Gale Crater on Mars. Today’s sample will be dropped for chemical analysis into a tiny lab inside the chamber known as SAM, which stands for Sample Analysis at Mars. Another SAM lab is on Mars, inside the belly of Curiosity. The SAM lab analyzes rock and soil samples in search of organic matter, which on Earth is usually associated with life. Mars-in-a-box is kept at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

This is Goddard engineer Ariel Siguelnitzky. He is showing how far he has to drop the sample, from the top of the test chamber to the sample collection cup, a small capsule about half an inch (1 centimeter) tall (pictured right below). On Mars, there are no engineers like Siguelnitzky, so Curiosity’s arm drops soil and rock powder through small funnels on its deck. In the photo, Siguelnitzky’s right hand is pointing to a model of the tiny lab, which is about the size of a microwave. SAM will heat the soil to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius) to extract the gases inside and reveal the chemical elements the soil is made of. It takes about 30 minutes for the oven to reach that super high temperature.

Each new sample is dropped into one of the white cups set into a carousel inside SAM. There are 74 tiny cups. Inside Curiosity’s SAM lab, the cups are made of quartz glass or metal. After a cup is filled, it’s lifted into an oven inside SAM for heating and analysis.

Amy McAdam, a NASA Goddard geochemist, hands Siguelnitzky the sample. Members of the SAM team made it in the lab using Earthly ingredients that duplicate Martian rock powder. The powder is wrapped in a nickel capsule (see photo below) to protect the sample cups so they can be reused many times. On Mars, there’s no nickel capsule around the sample, which means the sample cups there can’t be reused very much.

SAM needs as little as 45 milligrams of soil or rock powder to reveal the secrets locked in minerals and organic matter on the surface of Mars and in its atmosphere. That’s smaller than a baby aspirin!

Siguelnitzky has pressurized the chamber – raised the air pressure to match that of Earth – in order to open the hatch on top of the Mars box.

Now, he will carefully insert the sample into SAM through one of the two small openings below the hatch. They’re about 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) across, the same as on Curiosity. Siguelnitzky will use a special tool to carefully insert the sample capsule about two feet down to the sample cup in the carousel.

Sample drop.

NASA Goddard scientist Samuel Teinturier is reviewing the chemical data, shown in the graphs, coming in from SAM inside Mars-in-a-box. He’s looking to see if the lab-made rock powder shows similar chemical signals to those seen during an earlier experiment on Mars.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Space Telescope Gets to Work

Our latest space telescope, Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), launched in April. This week, planet hunters worldwide received all the data from the first two months of its planet search. This view, from four cameras on TESS, shows just one region of Earth’s southern sky.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) captured this strip of stars and galaxies in the southern sky during one 30-minute period in August. Created by combining the view from all four of its cameras, TESS images will be used to discover new exoplanets. Notable features in this swath include the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds and a globular cluster called NGC 104. The brightest stars, Beta Gruis and R Doradus, saturated an entire column of camera detector pixels on the satellite’s second and fourth cameras.

Credit: NASA/MIT/TESS

The data in the images from TESS will soon lead to discoveries of planets beyond our solar system – exoplanets. (We’re at 3,848 so far!)

But first, all that data (about 27 gigabytes a day) needs to be processed. And where do space telescopes like TESS get their data cleaned up? At the Star Wash, of course!

TESS sends about 10 billion pixels of data to Earth at a time. A supercomputer at NASA Ames in Silicon Valley processes the raw data, turning those pixels into measures of a star’s brightness.

And that brightness? THAT’S HOW WE FIND PLANETS! A dip in a star’s brightness can reveal an orbiting exoplanet in transit.

TESS will spend a year studying our southern sky, then will turn and survey our northern sky for another year. Eventually, the space telescope will observe 85 percent of Earth’s sky, including 200,000 of the brightest and closest stars to Earth.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Dark Matter 101: Looking for the missing mass

Here’s the deal — here at NASA we share all kinds of amazing images of planets, stars, galaxies, astronauts, other humans, and such, but those photos can only capture part of what’s out there. Every image only shows ordinary matter (scientists sometimes call it baryonic matter), which is stuff made from protons, neutrons and electrons. The problem astronomers have is that most of the matter in the universe is not ordinary matter – it’s a mysterious substance called dark matter.

What is dark matter? We don’t really know. That’s not to say we don’t know anything about it – we can see its effects on ordinary matter. We’ve been getting clues about what it is and what it is not for decades. However, it’s hard to pinpoint its exact nature when it doesn’t emit light our telescopes can see.

Misbehaving galaxies

The first hint that we might be missing something came in the 1930s when astronomers noticed that the visible matter in some clusters of galaxies wasn’t enough to hold the cluster together. The galaxies were moving so fast that they should have gone zinging out of the cluster before too long (astronomically speaking), leaving no cluster behind.

Simulation credit: ESO/L. Calçada

It turns out, there’s a similar problem with individual galaxies. In the 1960s and 70s, astronomers mapped out how fast the stars in a galaxy were moving relative to its center. The outer parts of every single spiral galaxy the scientists looked at were traveling so fast that they should have been flying apart.

Something was missing – a lot of it! In order to explain how galaxies moved in clusters and stars moved in individual galaxies, they needed more matter than scientists could see. And not just a little more matter. A lot . . . a lot, a lot. Astronomers call this missing mass “dark matter” — “dark” because we don’t know what it is. There would need to be five times as much dark matter as ordinary matter to solve the problem.

Holding things together

Dark matter keeps galaxies and galaxy clusters from coming apart at the seams, which means dark matter experiences gravity the same way we do.

In addition to holding things together, it distorts space like any other mass. Sometimes we see distant galaxies whose light has been bent around massive objects on its way to us. This makes the galaxies appear stretched out or contorted. These distortions provide another measurement of dark matter.

Undiscovered particles?

There have been a number of theories over the past several decades about what dark matter could be; for example, could dark matter be black holes and neutron stars – dead stars that aren’t shining anymore? However, most of the theories have been disproven. Currently, a leading class of candidates involves an as-yet-undiscovered type of elementary particle called WIMPs, or Weakly Interacting Massive Particles.

Theorists have envisioned a range of WIMP types and what happens when they collide with each other. Two possibilities are that the WIMPS could mutually annihilate, or they could produce an intermediate, quickly decaying particle. In both cases, the collision would end with the production of gamma rays — the most energetic form of light — within the detection range of our Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

Tantalizing evidence close to home

A few years ago, researchers took a look at Fermi data from near the center of our galaxy and subtracted out the gamma rays produced by known sources. There was a left-over gamma-ray signal, which could be consistent with some forms of dark matter.

While it was an exciting finding, the case is not yet closed because lots of things at the center of the galaxy make gamma rays. It’s going to take multiple sightings using other experiments and looking at other astronomical objects to know for sure if this excess is from dark matter.

In the meantime, Fermi will continue the search, as it has over its 10 years in space. Learn more about Fermi and how we’ve been celebrating its first decade in space.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Sixty Years of Exploration, Innovation, and Discovery!

Exactly sixty years ago today, we opened our doors for the first time. And since then, we have opened up a universe of discovery and innovation.

There are so many achievements to celebrate from the past six decades, there’s no way we can go through all of them. If you want to dive deeper into our history of exploration, check out NASA: 60 Years and Counting.

In the meantime, take a moonwalk down memory lane with us while we remember a few of our most important accomplishments from the past sixty years!

In 1958, President Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which effectively created our agency. We officially opened for business on October 1.

To learn more about the start of our space program, watch our video: How It All Began.

Alongside the U.S. Air Force, we implemented the X-15 hypersonic aircraft during the 1950s and 1960s to improve aircraft and spacecraft.

The X-15 is capable of speeds exceeding Mach 6 (4,500 mph) at altitudes of 67 miles, reaching the very edge of space.

Dubbed the “finest and most productive research aircraft ever seen,” the X-15 was officially retired on October 24, 1968. The information collected by the X-15 contributed to the development of the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, and Space Shuttle programs.

To learn more about how we have revolutionized aeronautics, watch our Leading Edge of Flight video.

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on the moon. The crew of Apollo 11 had the distinction of completing the first return of soil and rock samples from beyond Earth.

Astronaut Gene Cernan, during Apollo 17, was the last person to have walked on the surface of the moon. (For now!)

The Lunar Roving Vehicle was a battery-powered rover that the astronauts used during the last three Apollo missions.

To learn more about other types of technology that we have either invented or improved, watch our video: Trailblazing Technology.

Our long-term Earth-observing satellite program began on July 23, 1972 with the launch of Landsat 1, the first in a long series (Landsat 9 is expected to launch in 2020!) We work directly with the U.S. Geological Survey to use Landsat to monitor and manage resources such as food, water, and forests.

Landsat data is one of many tools that help us observe in immense detail how our planet is changing. From algae blooms to melting glaciers to hurricane flooding, Landsat is there to help us understand our own planet better.

Off the Earth, for the Earth.

To learn more about how we contribute to the Earth sciences, watch our video: Home, Sweet Home.

Space Transportation System-1, or STS-1, was the first orbital spaceflight of our Space Shuttle program.

The first orbiter, Columbia, launched on April 12, 1981. Over the next thirty years, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour would be added to the space shuttle fleet.

Together, they flew 135 missions and carried 355 people into space using the first reusable spacecraft.

On January 16, 1978, we selected a class of 35 new astronauts--including the first women and African-American astronauts.

And on June 18, 1983, Sally Ride became the first American woman to enter space on board Challenger for STS-7.

To learn more about our astronauts, then and now, watch our Humans in Space video.

Everybody loves Hubble! The Hubble Space Telescope was launched into orbit on April 24, 1990, and has been blowing our minds ever since.

Hubble has not only captured stunning views of our distant stars and galaxies, but has also been there for once-in-a-lifetime cosmic events. For example, on January 6, 2010, Hubble captured what appeared to be a head-on collision between two asteroids--something no one has ever seen before.

In this image, Hubble captures the Carina Nebula illuminating a three-light-year tall pillar of gas and dust.

To learn more about how we have contributed to our understanding of the solar system and beyond, watch our video: What’s Out There?

Cooperation to build the International Space Station began in 1993 between the United States, Russia, Japan, and Canada.

The dream was fully realized on November 2, 2000, when Expedition 1 crew members boarded the station, signifying humanity’s permanent presence in space!

Although the orbiting lab was only a couple of modules then, it has grown tremendously since then!

To learn more about what’s happening on the orbiting outpost today, visit the Space Station page.

We have satellites in the sky, humans in orbit, and rovers on Mars. Very soon, we will be returning humankind to the Moon, and using it as a platform to travel to Mars and beyond.

And most importantly, we bring the universe to you.

What are your favorite NASA moments? We were only able to share a few of ours here, but if you want to learn about more important NASA milestones, check out 60 Moments in NASA History or our video, 60 Years in 60 Seconds.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

NASA’s 60th Anniversary: What’s Out There

In the past 60 years, we’ve advanced our understanding of our solar system and beyond. We continually ask “What’s out there?” as we advance humankind and send spacecraft to explore. Since opening for business on Oct. 1, 1958, our history tells a story of exploration, innovation and discoveries. The next 60 years, that story continues. Learn more: https://www.nasa.gov/60

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Studying Sediments in Space

An International Space Station investigation called BCAT-CS studies dynamic forces between sediment particles that cluster together.

For the study, scientists sent mixtures of quartz and clay particles to the space station and subjected them to various levels of simulated gravity.

Conducting the experiment in microgravity makes it possible to separate out different forces that act on sediments and look at the function of each.

Sediment systems of quartz and clay occur many places on Earth, including rivers, lakes, and oceans, and affect many activities, from deep-sea hydrocarbon drilling to carbon sequestration.

Understanding how sediments behave has a range of applications on Earth, including predicting and mitigating erosion, improving water treatment, modeling the carbon cycle, sequestering contaminants and more accurately finding deep sea oil reservoirs.

It also may provide insight for future studies of the geology of new and unexplored planets.

Follow @ISS_RESEARCH to learn more.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

10 Things: Why Cassini Mattered

One year ago, on Sept. 15, 2017, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft ended its epic exploration of Saturn with a planned dive into the planet’s atmosphere--sending back new science to the last second. The spacecraft is gone, but the science continues. Here are 10 reasons why Cassini mattered...

1. Game Changers

Cassini and ESA (European Space Agency)’s Huygens probe expanded our understanding of the kinds of worlds where life might exist.

2. A (Little) Like Home

At Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, Cassini and Huygens showed us one of the most Earth-like worlds we’ve ever encountered, with weather, climate and geology that provide new ways to understand our home planet.

3. A Time Machine (In a Sense)

Cassini gave us a portal to see the physical processes that likely shaped the development of our solar system, as well as planetary systems around other stars.

4. The Long Run

The length of Cassini’s mission enabled us to observe weather and seasonal changes over nearly half of a Saturn year, improving our understanding of similar processes at Earth, and potentially those at planets around other stars.

5. Big Science in Small Places

Cassini revealed Saturn’s moons to be unique worlds with their own stories to tell.

6. Ringscape

Cassini showed us the complexity of Saturn’s rings and the dramatic processes operating within them.

7. Pure Exploration

Some of Cassini’s best discoveries were serendipitous. What Cassini found at Saturn prompted scientists to rethink their understanding of the solar system.

8. The Right Tools for the Job

Cassini represented a staggering achievement of human and technical complexity, finding innovative ways to use the spacecraft and its instruments, and paving the way for future missions to explore our solar system.

9. Jewel of the Solar System

Cassini revealed the beauty of Saturn, its rings and moons, inspiring our sense of wonder and enriching our sense of place in the cosmos.

10. Much Still to Teach Us

The data returned by Cassini during its 13 years at Saturn will continue to be studied for decades, and many new discoveries are undoubtedly waiting to be revealed. To keep pace with what’s to come, we’ve created a new home for the mission--and its spectacular images--at https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/cassini.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.