Q587p - 587

More Posts from Q587p and Others

Yup, that’s about twitter

And we have XKCD about this 😅

I understand why alchemists invented, and modern fiction writers use, systems with a few understandable Elements like Earth / Fire / Air / Water / Light / Dark.

I understand why even most nerds don't bother to study the Elements in real life. There's too many of them, and they don't neatly correspond to meaningful aspects of macro-level existence.

But just once I'd like to read a worked magical system where the author has looked up the properties of the real Elements, has put in all the work to build up a system of plausible-sounding correspondences, and the protagonist is a rare dual-element Tellurium-Iodine wizard.

З деякими моментами дуже б посперечався, але най буде.

це не мій текст. я його десь скопіпастила ще п'ять років тому. чи допомогло? пфффбгггг

але кожен з цих пунктів я б викарбувала на стіні.

***

32 вывода к 32 годам

1. Страшно всем. И красивым, и талантливым, и умным, и везучим. Начинать новое. Выходить из привычного круга. Рисковать. Делать что-то, к чему еще не привык. Страшно за близких. За дело. За свою жизнь, если прижмет. И много чего еще. Страх будет и дальше.

Сколько бы ни было опыта, практики, уверенности, признания, денег, таланта, но каждый раз замахиваясь на новую высоту, каждый раз выходя на сцену, каждый раз, оборачиваясь на близких — в той или иной степени будет страх. Это нормально. Это значит, что ты еще жив. И значит, нужно идти вперед. Через страх. А не пытаться полностью от него избавиться.

2. Жизни без перемен не существует. Стабильность иллюзорна. Мы постоянно находимся в движении. Мы постоянно меняемся внешне и внутреннее, эти процессы не прекращаются ни на секунду. И секунды, как меры измерения, здесь даже много. Процессы идут каждое мгновение. Это множество секунд. Вопрос: «Меняться или не меняться?» у здравомыслящего человека стоять не может. Только: «Имею ли я отношение к этим изменениям и в какой мере?»

3. Быстро — это медленно, но без перерыва. Не нужно быстро, интенсивно, круто, очень мощно. Достаточно всего лишь регулярно. Самое главное — держать ритм. По чуть-чуть, но со стабильной последовательностью. А через какое-то время, со стороны, это будет выглядеть, как быстро, интенсивно, круто и очень мощно.

4. Создавать больше, чем потреблять. Иначе, все. Беспросветная жизнь потребителя, витиевато сплетающаяся в многозначительный вывод: «Все хорошо, но ничего хорошего». Человек должен что-то делать. Добровольно и любя. Это формула его душевного здоровья. А бонусом, что любопытно — это единственный способ получать удовольствие от потребления, которое не будет его разрушать. Можно считать этот процесс — здоровым психическим метаболизмом.

5. Сегодня — это то, что ты делал и думал вчера, а завтра — это то, что ты делаешь и думаешь сегодня. Эту фразу нужно повторять, как мантру до тех пор, пока не дойдет, что твои родители не имеют отношения к твоим взрослым проблемам. Во всяком случае, они не виноваты, что некому сменить пластинку в твоей голове, которая заела с детства.

6. Никаких гарантий нет. Базовое правило мироздания, через которое нужно пропускать все свои решения и планы.

7. Эпоха сокровенных знаний, которые могут что-то изменить, закончена. Настала эра информационной гигиены. Уже лет пять, как знания не являются главной валютой в вопросе достижений и какого-либо осмысленного существования. Интернет их обесценил своей доступностью. На смену пришла концентрация. Способность удерживать внимание на задаче и не расплескивать интерес — вот кто правит. А этот навык находится в прямой зависимости от информационного шума, который сегодня повсюду. Чем больше словесного мусора вокруг — тем слабее фокус. Чем больше чужих мыслей, тем тише собственный голос. Постоянное нахождение в интернет-потоке атрофирует способность к самоосознанию, подменяя суть концепциями о том, что ею является.

8. Радость и удовольствие — не одно и то же. Мы никогда не получаем радости от шоколадного торта, фужера вина или сигаретки. Мы не получаем радости от новых сапог или духов. Важно называть вещи своими именами — мы получаем удовольствие. А тут уже совсем другая химия. Природа этого чувства очень скоротечна и неразрывно связана с последующей неудовлетворенностью, скукой, пресыщенностью и желанием новой порции. Не страшно отказать себе в удовольствиях, страшно не познать радость.

9. Страдания существуют. Будда был все-таки прав. Страдания существуют. Страдают все. И те, у кого ничего нет, и те, у кого есть все. А кто конкретно в эту минуту не страдает, уйдет в боль в следующую, как только изменится курс доллара, произойдет теракт, получит в ответ, что его не любят, увидит грязный подъезд, не дождется ответа на сообщение, не получит денег или по любому другому дуновению ветерка. Страдания существуют. И всегда без повода, если вспомнить финал любого человеческого существа.

10. Быть счастливыми могут не все. Каждый ли человек может быть счастливым? Да, разумеется! Но это в теории. На практике стабильно счастливыми, то есть спокойными, уравновешенными, благостными, если хотите, могут быть только те, кому доступна дисциплина ума. Чей ум способен (натренирован) не дергаться по всем многочисленным поводам, которые его окружают. Кто может оставаться в равновесии радости не только в штиль, но и в порыве неприятных ситуаций. В противном случае, все бесконечные поводы от царапины на твоем авто будут выкидывать тебя в боль, раздражение и тревогу. И это всего лишь какая-то машина, а есть же ситуации и посерьезнее. Счастливым такой загнанный ум, реагирующий на любое происшествие, можно назвать лишь в статусе Инстаграма.

11. Радость — это равновесие ума. Скажите мне это лет так 5 назад, я бы покрутила у виска. Когда тебе днем и ночью мечтается большая светлая любовь, дружная семья, интересное доходное дело, возможность работать на себя, а не на другого, насыщенная путешествиями жизнь, кажется, что, все-таки, ты имеешь какие-то представления о радости, как минимум, о собственной. Да, ты сейчас во многом не удовлетворен, да что-то может вывести тебя из себя, да ты страдаешь. Так это и понятно. Но ты знаешь к чему стремиться. Ты знаешь, где твоя осязаемая непреходящая радость, заглядываясь на свои, столь манящие, мечты. Радость — это состояние полного равновесного покоя ума, которое достигается при освобождении от слепых (автоматических) реакций этого самого ума. Здоровый, возможно единственный, способ познать (и развивать) такое состояние во взрослом возрасте — это глубокая медитация наблюдения.

12. Фрукты — не кислотная, а щелочная еда. Если по-научному, свежие спелые фрукты и почти все овощи вызывают в организме щелочную реакцию и помогают нейтрализовать избыток кислоты в нем, а крахмал, сахар, мясопродукты, жиры, масла, молочная продукция, наоборот, организм закисляют. Полное описание есть в таблице Н. Уокера и Р. Поупа, которая доступна через гугл.

13. «Мое тело само знает, что ему лучше» — одна из самых коварных ловушек ума. Тело алкоголика хочет выпить, тело курильщика мечтает о сигаретке, наше тело жаждет шоколада и картошки-фри. О каком «лучше знает» все говорят? Также, как и ум живет автоматическими реакциями, не давая человеку делать элементарные подвижки в своей жизни, так и тело подчиняется привычкам и хаотичным импульсам вожделения.

14. Питание влияет не только на наше тело, но и на наше сознание. Подобно алкоголю, который заметно изменяет наше сознание, притупляя его, некоторые продукты несут схожий эффект, но в менее выраженной и зачастую неосознаваемой форме. Еда может замедлять и расфокусировать голову, ослабляя контроль, силу осознанности и ясность восприятия. Слегка «затуманенное» состояние становится уровнем нормы, позволяя человеку забыть, что значит легкость и ясность на самом деле. Наиболее «свободная» еда — это свежие овощи и фрукты, а также растительная пища и злаки, приготовленные простым способом с минимальным содержанием масла, приправ и соли.

15. Денег нужно столько, чтобы о них не думать. Деньги не решают главный вопрос человечества — они не делают своего владельца счастливым. Но возможность о них не думать, как минимум в быту, существенно высвобождает энергию для других процессов.

16. Мы все одинаковые намного больше, чем разные. Значение личной уникальности сильно преувеличенно и не дает нам быстро решать свои проблемы. Все ответы и решения давно существуют, а зацикленность на собственной неповторимости не дает человеку задвинуть свое эго туда, где ему было бы полезно всегда находиться и без помех воспринимать окружающую его реальность со всеми ответами и подсказками.

17. Зависимость лечится только 100% отказом. Нельзя выпить один фужер вина, если ты алкоголик. Нельзя иногда курить, если пытаешься бросить. Тебя будет скручивать постоянно. Взлеты и падения. Срывы. В вопросах психоэнергетических «крючков» нет полутонов. И это правило незыблемо для зависимостей всех типов.

18. Состояния внутренней 100% готовности к переменам не существует. Мы всегда до конца не готовы к поворотам и изменениям. Всегда есть веские «но» и поводы немного отложить до более благоприятной ситуации. Бесполезно ждать однозначного внутреннего согласия, нужно решаться, опираясь скорее на «пора», чем на эфемерную готовность.

19. Жизнь — это книга, первые главы которой были написаны не тобой. Да, и последующие — тоже, чаще всего.

Мы состоим из убеждений и моделей окружающего нас мира, а мир этот — не абстрактная планета Земля, а вполне конкретный подъезд, офис, дом — место, где мы проводим время. Это друзья, коллеги, родители, продавцы в магазине, с которыми сталкиваешься каждый вечер. Это лента в социальных сетях и так называемые друзья из фейсбука. Мы впитываем взгляды, позиции, точки зрения просто автоматически, мы вдыхаем их с воздухом и становимся такими же или наоборот противоположными, что тоже автоматический момент отрицания. В детстве этот процесс полностью неуправляем. Суть нашей личности собирали другие люди и осознанный родительский вклад (если он вообще был) там далеко не преобладает. То, что мы считаем собой и то, что надо бояться потерять по версии некоторых психологов, — всего лишь в той или иной степени красоты мозаики от нашего окружения. Терять нечего. По-моему, отличная новость. Можно перекроить все в какую угодно сторону.

20. Результат — это количество попыток. А не один меткий выстрел. И уж точно не удача при долгосрочной перспективе.

21. То, что тебе помогало на одном этапе может оказаться тормозом для выхода на следующий. Способность к кардинальным переменам характеризуется возможностью отказываться. Но не только от того, что тебе мешает. Порой очень важно отказаться от того, что тебе помогало в прошлом. Простой пример: правила малого бизнеса не работают в среднем. Расти без отказа от части из них, пусть даже они поднимали процесс вчера, — невозможно. Тоже и с человеческой личностью — ее установками, планами.

22. За зоной комфорта находится зона дискомфорта. А не коробка шоколадных конфет.

23. Жизни без цели не существует. Также, как и состояния без перемен. Вопрос лишь в том: ставишь ли ты эти цели сам или отдаешь на откуп инстинктам (неосознанным целям).

24. Лени — не существует. Есть нелюбимые занятия, нехватка энергии и отсутствие масштабного видения, чтобы захватывало дух от открывающихся перспектив. А лени нет.

25. Себя невозможно найти, себя можно только создать. Искать нечего и некого. Ты всегда есть здесь и сейчас. А твой путь — это то, что у тебя под ногами в данную конкретную секунду, не более того. Тот самый «свой» путь отличается от того, чем он не является только фактом осознанности идущего, который прокладывает пусть и небольшие, но вполне осязаемые цели. Когда эти цели определяют другие люди или они прорастают хаотично через слово «должен» — никакого пути нет, есть набор разношерстных неприкаянных эпизодов.

26. Алкоголь не нужен. Вообще.

27. Нереализованный потенциал причиняет боль. И бесполезно прятаться от этого факта в выбранный уровень комфорта или красивые философские концепции, те же истории про женственность, материнство и прочее. За каждый талант с нас спросится.

28. Банки должны платить тебе, а не ты им. Это единственно возможное финансовое здоровье. Никогда никогда никогда не стоит покупать то, на что не заработал. Никогда. Во всяком случае, если грезишь о серьезных переменах. Мы платим банку не только деньгами, но и своей свободной энергией. Пространства для риска и авантюрных подвижек практически не остается. Прорыв из такого состояния (особенно на новый финансовый уровень) вряд ли возможен.

29. Две способности, которыми нужно овладеть, как можно раньше: умение напрягаться и умение расслабляться.

Любое движение требует напряжения сил в тот или иной момент. Если идти на него нехотя, по нужде — будет расходоваться в два раза больше энергии. Часть на само усилие, остальное — на психическое напряжение. На внутреннюю борьбу. Отсюда необходимость научиться напрягаться по желанию, полюбить свое усилие. При способности напрягаться добровольно, видя в этом исключительно положительный аспект, количество потраченных сил сократится в разы. Будет получаться больше и легче. А умение расслабляться — принимать реальность такой какая она есть, отпускать собственные ожидания, развязывая внутренние узлы и снимая телесное напряжение — второе крыло, без которого на одном напряжении далеко не продвинешься.

30. Два ответа, которым нужно научиться, как можно раньше: «Да» и «Нет». Говорить «Да» ситуациям и людям несмотря на отсутствие гарантий, полной внутренней готовности и различные внешние обстоятельства. И говорить «Нет» в первую очередь самому себе — своим слабостям, страхам и внутренней распущенности. И лишь далеко потом — другим людям.

31. Крутые штуки отличаются от хороших способностью делающего забывать себя. Творец отличается от человека, который что-то неплохо делает тем, что ставит дело выше себя, растворяя в процессе свое эго. И делает это осознанно и любя, а не по отсутствию выбора или чувству долга. Так один маркетолог может быть истинным музыкантом в профессии, а иной музыкант так на всю жизнь и остается тем, кто имеет дело с музыкой.

32. Каждый встреченный на пути знак всегда имеет минимум 3 толкования. 1. Может быть это действительно знак! 2. Может быть ты бредишь и притягиваешь факты за уши. 3. А может быть это испытание — явление противоположное знаку — попытка отвести от выбранного пути, как проверка искренности твоего решения и силы намерения.

Decomposing Undertale’s Music Composition Structure

The Undertale soundtrack is enormously fun, expressive, and symbolically meaningful. It also, interestingly enough, is composed with a very small pallet of compositional techniques. The majority of tracks are written the same way. An astonishing number of Undertale’s OST songs contain most/all of the following elements:

An ostinato. If there is not an ostinato, there is still a background line that maintains repeated rhythmic and pitch movement patterns.

An ostinato introduction paradigm. The ostinato is introduced first, then the midground, then the melody.

Melody made of parallel periods. The melody consists of eight bar periods with a parallel question and answer phrase. That is, the first line of the melody and the second line of the melody start similarly and in a way “mirror” each other.

Everything melodic is repeated twice. Melodic structural units are played twice in a row before introducing something new.

Binary Form. The pieces overall consist of a Binary AABB form. That is, the piece starts with one big melodic theme and then ends with a second big melody theme.

Below, I will describe in depth how to structure and develop a “prototypical” Undertale track piece.

Step 1: Create an ostinato

An ostinato is a short unit of music that plays on repeat throughout a piece. The notes and rhythms stay exactly the same and are repeated over and over without stop. A good example of an ostinato is Pachelbel’s canon. The cellos play the same notes on repeat from start to end. That’s the ostinato.

A dramatically high percentage of the pieces in Toby Fox’s Undertale soundtrack make use of an ostinato, including but not limited to: “Fallen Down,” “Ruins,” “Ghost Fight,” “Heartache,” “Snowy,” “Snowdin Town,” “Bonetrousle,” “Nyeh Heh Heh!”, “Dummy!”, “Death by Glamour,” “An Ending,” “Here We Are,” “Amalgam,” “Gaster’s Theme,” “Battle Against a True Hero,” “Power of NEO,” and “Megalovania.”

To give an example, below is the notation to the four measure ostinato in “Megalovania”. You can hear this ostinato played by itself at the very beginning from 0:00-0:07. Note that when the bass line comes in 0:07, it is also a four measure repeating unit that recurs throughout much of “Megalovania.”

The first half of “Battle Against a True Hero” uses the ostinato I have transcribed below. It comes it right at the start of the piece (0:00) with the solo piano. The second half of the track is a second, different ostinato. Like “Megalovania,” the bass part is also an ostinato playing alongside the piano.

Below, the ostinato which starts (0:00) “Death by Glamour.”

The Ostinato in “Ruins” and “An Ending”, also introduced right at the start 0:00.

The point of the matter is, while ostinato is one compositional device that’s been used for centuries, it’s not present as frequently as Toby Fox himself uses it. He has an unusually high percentage of ostinato pieces; the Undertale soundtrack relies heavily on it.

If not an ostinato, something ostinato-like

Sometimes the background or mid-ground (that is, the part of the music that is not the melody but not the basic background) in an Undertale track is not a strict ostinato. That is, the same notes and pitches don’t repeat perfectly over and over and over again. However, when Fox doesn’t use a perfect ostinato, there is almost always something ostinato-like, a repeated rhythmic pattern that has an embedded pitch pattern as well. The notes might not be 100% the same every time they repeat, but it’s still a noticeable pattern.

For example, “Spear of Justice” and “NGAHHH!!” have a dramatic bass line that is built on a recurring rhythm. However, the chords of that bass line change around, so the notes aren’t exactly the same every time you hear an iteration of the rhythmic pattern. The notes usually arpeggiate (move up and down) the same way, though, along the same rhythms.

“Your Best Friend” is another example. Below is part of the accompaniment for that song. If you notice, there is a general four note pattern in which the notes move up and down the same way. The individual notes might change (as I have circled), but the pattern rhythmically and generally pitch-wise remains the same.

Step 2: Introduce the ostinato, then more accompaniment, then the melody and jam

What’s interesting is that it’s not just that there’s a liberal presence of ostinatos in the soundtrack, but that they’re frequently introduced, used, and implemented the same way each time. There is a certain “ostinato introduction paradigm” Toby Fox likes to use.

First, the ostinato is introduced by itself. Then, other accompaniment (non-melody) is layered on top of the ostinato. Last, the melody jumps in, oftentimes with the explosion of a more energetic drum rhythm. Sometimes the second step I mentioned is skipped, but this sort of pattern nevertheless manifests itself in piece after piece.

For example, “Battle Against a True Hero” begins with a solo piano playing the ostinato. After it plays the ostinato once, we get some mid-ground music at 0:05. After the mid-ground is introduced, Toby Fox inserts in the melody at 0:18. The drums kick in at the same time as the melody at 0:18.

Now listen to “Death by Glamour.” The ostinato starts by itself in a single instrument (also, amusingly, a piano). A few instruments are added on top of it between 0:06 and 0:25. At 0:25, the entire music ensemble is in and a melody is introduced. Though there was a kick drum earlier, it’s at 0:20, near to the introduction of the melody, that the drums really start going.

Exact same pattern.

Now listen to the start of “Megalovania.” It again begins with a single instrument line, a four measure ostinato. Then, at 0:07, a bass line is added below it. After that cycles through once, the entire ensemble jumps in at 0:15, the drums kick up, and we’re off to the races.

Exact same pattern.

And if you want more fun listening, check out “Dummy!” Ostinato at start. Midground at 0:07 with a bare bass drum. Melody at 0:22 with full drum set. Same thing happens in “Ghost Fight.” Same thing happens in “Snowdin Town.” Same thing happens in “Thundersnail.” Same thing happens in “Amalgam.” Same thing happens with many, many more tracks throughout the Undertale OST.

With the rhythmic patterned accompaniments that are not quite ostinatos, you still see the same sort of “ostinato” introduction paradigm. Examples of this include “Waterfall,” “Alphys,” “Temmie Village,” and “Metal Crusher.”

Toby Fox uses not only an ostinato frequently, but he also often uses this particular technique of introducing and developing the ostinato. It’s a stock trick of his. These pieces are written and developed the same way.

So the ostinato describes the accompaniment pattern Fox likes to utilize. But what about the melody? It turns out there are a lot of patterns Fox uses for melody, too.

Step 3: The melody consists of two parallel lines

A phrase is a line that sounds sort of like a musical sentence or, well, a phrase. It has a notable start and end point. If you were singing a phrase that had lyrics to it, the phrase would be one line of lyrics.

Toby Fox’s phrases are always four measures long. They also always come in pairs. This is a very common musical composition structure. A pair of phrases in fact has its own technical term - it’s called a period.

There are several different types of periods in music composition, but Toby Fox almost invariably uses the same one every time. He composes a parallel question and answer period.

“Question and answer” means that the second phrase sounds like it is resolving something the first phrase introduces. The first musical phrase ends in a sort of “question” - that is, it doesn’t sound finished when you reach the end of it. Just like a spoken question has raised intonation at the end (in English), it sounds like the musical phrase’s question is incomplete. The second musical phrase ends in an “answer” - that is, it ends the notes with a resolute conclusion and landing by the end. It sounds like the lowered, resolving intonation you hear when someone talking answers a question with a declarative sentence.

Now, phrases being question and answer is still pretty common in the music composition world. But what you also see in Undertale is that the phrases are parallel phrases, too. That is, the first phrase starts the same way that the second phrase does.

I could practically list the entire Undertale soundtrack for being culprit to the parallel question and answer eight bar periods. But I’ll pull out just a few examples to concretely show what’s going on.

One of the best examples of this melodic form is in “Your Best Friend” because the entire melody consists of that eight bar parallel question and answer period.

Period 1 is the first four measures, notated on the top line. Period 2 is the second four measures, notated on the bottom line. Notice that Periods 1 and 2 start the same way, and in fact the first 13 notes from each are exactly the same. Even when they do diverge pitches at the end, they still keep the same rhythm. Period 1 is considered a question because it ends on an F, which is the fifth scale degree of the key signature, a Bb, so Period 1 ends on the V chord. The V chord is considered to be an incomplete sound when you stop there. It’s a question. But Period 2 ends on the I chord with the first scale degree, the Bb, which is an answer or resolution.

To visually show another example, here’s “Nyeh Heh Heh!” / “Bonetrousle”:

In “Nyeh Heh Heh!”, only the first four notes of Period 1 completely match the pitches of those notes in Period 2. However, if you look at my arrows, you’ll notice we keep the same parallel up and down motion throughout each of the lines. The pitches still move directionally in the same way throughout the lines. Especially since the two phrases start the same characteristic way, and then bounce up and down the same way, we audiences hear a parallel question and answer.

But this structure is really everywhere. The dating themes. “Snowy.” “Spear of Justice.” You name it. It’s there.

Step 4: Everything melodic is repeated twice

Music has a lot of different structural units of different sizes. There are small units in music, like a four measure phrase. There are larger units, like an entire thematic section, which is usually labeled “A” or “B”. When Toby Fox has distinct melodic (or ostinatic) material, he repeats it twice before introducing something new.

Screencap of “Spear of Justice” sheet music from Jester Musician.

“Spear of Justice” is a perfect example of this “repeat in twos” paradigm. The song’s introduction consists of a four bar phrase repeated twice (0:00-0:05 and 0:05-0:10). Then the bass and drums come in. We hear a four bar unit again repeated twice (0:10-0:15 and 0:15-0:21). Then we switch key signatures. We hear a four bar unit again repeated twice (0:26 and 0:26-0:30). There is a little tag at the end finishing the A section and leading into the B section.

The first two phrases of the B section are exactly the same as one another and can be heard from 0:35-0:41 and 0:41-0:47. The next two phrases are also exactly the same as one another and can be heard from 0:47-0:53 and 0:53-0:58. So what Toby Fox does is play one phrase, repeat it, play a new phrase, repeat it. Rule of two. Then, he repeats this ENTIRE chunk from 0:35-0:58 again at 0:58-1:19. Here he’s got embedded layers of two.

For the rest of the B section, 1:19-1:31 is a period, and 1:31-1:41 is a repetition of that period. We get one last repetition of this period (which is identical to 1:31-1:41) before the song ends.

I could keep giving more examples of this exact same phenomenon throughout the soundtrack. “Home” has the opening guitar eight bar period repeated twice before the melody comes in. Then that melody is played twice. “Bonetrousle” has literally everything melodic duplicated in twos from start to finish. I’ll talk more about that piece later.

Toby Fox loves things in twos.

Step 5: Make it binary form

Binary form is a description of how a composition’s melodic themes are arranged. Binary form means that there are two main themes, “A” and “B”. The A theme gets played, thenb the B theme gets played, and then the piece is done. Usually in binary form, each theme gets played twice, so technically it’s AABB. This form is extremely, extremely common in Undertale.

To give just a few examples:

“Battle Against a True Hero” has an A section focusing on one melody and one ostinato from 0:00 to 1:35. Then, the rest of the piece is the B section, focusing on a second ostinato and melody.

“Nyeh Heh Heh!” and “Bonetrousle” are very simple, but technically you can divide them into two parts (by two periods that contain the entirety of the melody). The first period is the A section and is heard in Nyeh Heh Heh from 0:00-0:18 The second period is the B section and is heard from 0:18 to 0:32.

“Snowy” plays the same melody repeatedly from 0:00 to 1:02. The second half of the piece, the B section, goes from 1:02 to the end.

“Amalgam” has an A theme from 0:00 to 0:42. The B theme is 0:42 to the end.

“Enemy Approaching” has an A theme from 0:00 to 0:30. The B theme picks up from there and goes to the end of the piece.

“Here We Are” has an A section until about 0:43. When the piano takes over at that point, we enter the B theme. It continues more or less until the end of the piece.

A few pieces in Undertale have ternary structure, which means that you return to the A after the B is played. So, basically, they are ABA form. “Dummy!”, “Death by Glamour,” and “Heartbreak” are some examples of ternary structure in Undertale.

Examples: putting this all together

I will now go through several tracks in Undertale and show how they fall into all of these compositional steps and techniques. Lots of Undertale pieces really are written the same way.

Bonetrousle

Bonetrousle is introduced with a bass line that repeats every four notes. This pattern is basically an ostinato in the first half of the piece. However, it is to note the notes do change halfway through the song (at 0:30), and in the second half can only be described as a rhythmically patterned bass. Still, the accompaniment falls into exactly what I observed in the beginning of this analysis (Step 1).

The bass line is introduced by itself at 0:00 before the melody jumps in at 0:06 (Step 2).

The four note bass pattern is repeated four times (two twos) from 0:00-0:06 (Step 4).

The melody consists of a parallel question and answer period. The first phrase, the question, is 0:05-0:11, and the answer phrase is 0:12-0:18 (Step 3). I have already discussed how these are parallel phrases.

The period from 005:-0:18 is repeated at 0:18-0:30 - Rule of Twos (Step 4).

Bonetrousle consists of an A theme from 0:00-0:30 and a B from 0:30 to the end, making Bonetrousle binary form (Step 5).

The B theme consists of a period that is in parallel question and answer form. The question phrase is 0:30-0:37 and the answer phrase is 0:38-0:43 (Step 3).

The period from 0:30-0:43 is repeated at 0:43-0:58 because, of course, everything melodic has to be played twice (Step 4).

Battle Against a True Hero

The piece begins with an ostinato playing by itself (Step 1). The ostinato is, in a way, a parallel question and answer (Step 3).

The ostinato introduction paradigm is met. The ostinato plays by itself once from 0:00-0:05. Mid-ground music is added on top of the ostinato 0:05. After the mid-ground is introduced, Toby Fox inserts in the melody at 0:18. The drums kick in at the same time as the melody at 0:18 (Step 2).

The mid-ground introductory section is played twice at 0:05-0:11 and 0:11-0:18 (Step 4).

The melody is in periods with parallel phrases (Step 3).

The first two lines of the melody are played twice at 0:19-0:30 and 0:31-0:43 (Step 4).

The second two lines of the melody are played twice at 0:43-0:56 and 0:57-1:08. Then, this whole thing, 0:43-1:08, is then repeated from 1:08-1:34. Twos two twos everywhere (Step 4).

The A theme plays from 0:00-1:35. The B theme plays from 1:35 to the end, making “Battle Against a True Hero” binary form (Step 5).

The B theme starts with a new ostinato, introduced by itself in the piano (Step 1). At 1:45, strings are layered on top of the ostinato. At 1:54, everyone comes in, including the bass, the melody, and the drums. That’s the ostinato introduction paradigm being implemented a second time in this track (Step 2).

The B melody consists of a parallel question and answer period. The question can be heard from 1:55-2:03 and the answer is 2:03-2:13. If you notice, these are parallel phrases because they start the same way, and in fact have many notes in common before they end slightly differently (Step 3).

The melody is repeated twice 1:55-2:13 and 2:14-2:37 (Step 4).

Enemy Approaching

The main groove is introduced from 0:00-0:10. The rhythmic bass pattern heard at the bottom is consistent throughout the entire song (Step 1).

The accompaniment and mid-ground are introduced at 0:00-0:09. The melody kicks up at 0:10 with a fuller drum kit (Step 2).

The melody consists of a period with parallel question and answer phrases. The question can be heard from 0:10-0:15; the answer is 0:15-0:20. Note that both phrases start the same way - they’re definitely parallel and share a lot of notes in common (Step 3).

The period from 0:10-0:21 is repeated at 0:20-0:30.

You could call the first half of the melody from 0:00-0:30 an A and the second half of the melody from 0:30-0:56 a B, in which case you could argue this is binary structure (Step 4).

The period in B is a parallel question and answer. The question is 0:30-0:35 and the answer is 0:36-0:41 (Step 3).

The period from 0:30-0:41 is repeated at 0:41-0:56, because of course everything melodic has to be done in twos (Step 4).

These are just a few examples. There’s no need to go through every piece, but suffice it to say, my generalizations hold up to a large number of the tracks in the Undertale OST. Not every piece correlates to what I have mentioned, but many of them do.

It is really fascinating to see the diversity of melodies and moods that can be created from such a simple compositional structure. Yes, while the limited composition technique makes many tracks predictable and less original, the common form still shows us how one technique can be implemented multiple times to make many memorable and enjoyable songs. The structure also, in its own odd way, cements the pieces together to sound like a uniform soundtrack.

It is interesting to me, as a composer, to see how different composers structure their pieces. It allows us musicians to see what does and does not work. Toby Fox, while he sticks with one structure for a large portion of his pieces, uses a structure that works. By looking at this, we can listen, understand, and perhaps appreciate the solid structure within the Undertale OST.

Whenever Americans use Cryillic like. That. I just. Instantly shrivel up an cry

Writing Tips

Punctuating Dialogue

✧

➸ “This is a sentence.”

➸ “This is a sentence with a dialogue tag at the end,” she said.

➸ “This,” he said, “is a sentence split by a dialogue tag.”

➸ “This is a sentence,” she said. “This is a new sentence. New sentences are capitalized.”

➸ “This is a sentence followed by an action.” He stood. “They are separate sentences because he did not speak by standing.”

➸ She said, “Use a comma to introduce dialogue. The quote is capitalized when the dialogue tag is at the beginning.”

➸ “Use a comma when a dialogue tag follows a quote,” he said.

“Unless there is a question mark?” she asked.

“Or an exclamation point!” he answered. “The dialogue tag still remains uncapitalized because it’s not truly the end of the sentence.”

➸ “Periods and commas should be inside closing quotations.”

➸ “Hey!” she shouted, “Sometimes exclamation points are inside quotations.”

However, if it’s not dialogue exclamation points can also be “outside”!

➸ “Does this apply to question marks too?” he asked.

If it’s not dialogue, can question marks be “outside”? (Yes, they can.)

➸ “This applies to dashes too. Inside quotations dashes typically express—“

“Interruption” — but there are situations dashes may be outside.

➸ “You’ll notice that exclamation marks, question marks, and dashes do not have a comma after them. Ellipses don’t have a comma after them either…” she said.

➸ “My teacher said, ‘Use single quotation marks when quoting within dialogue.’”

➸ “Use paragraph breaks to indicate a new speaker,” he said.

“The readers will know it’s someone else speaking.”

➸ “If it’s the same speaker but different paragraph, keep the closing quotation off.

“This shows it’s the same character continuing to speak.”

MORE MUGS

moist von lipwig:

and adora belle:

AE pessimal:

when sybil buys vimes a mug:

when VETINARI buys vimes a mug, because no one will EVER believe it was him that bought it:

sybil:

angua:

carrot:

otto:

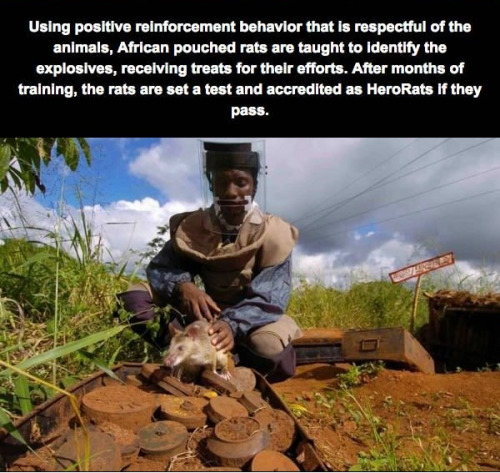

Hero Rats

Constellations and the Calendar

Did you recently hear that NASA changed the zodiac signs? Nope, we definitely didn’t…

…Here at NASA, we study astronomy, not astrology. We didn’t change any zodiac signs, we just did the math. Here are the details:

First Things First: Astrology is not Astronomy…

Astronomy is the scientific study of everything in outer space. Astronomers and other scientists know that stars many light-years away have no effect on the ordinary activities of humans on Earth.

Astrology, meanwhile, is something else. It’s the belief that the positions of stars and planets can influence human events. It’s not considered a science.

Some curious symbols ring the outside of the Star Finder. These symbols stand for some of the constellations in the zodiac. What is the zodiac and what is special about these constellations?

Imagine a straight line drawn from Earth though the sun and out into space way beyond our solar system where the stars are. Then, picture Earth following its orbit around the sun. This imaginary line would rotate, pointing to different stars throughout one complete trip around the sun – or, one year. All the stars that lie close to the imaginary flat disk swept out by this imaginary line are said to be in the zodiac.

The constellations in the zodiac are simply the constellations that this imaginary straight line points to in its year-long journey.

What are Constellations?

A constellation is group of stars like a dot-to-dot puzzle. If you join the dots—stars, that is—and use lots of imagination, the picture would look like an object, animal, or person. For example, Orion is a group of stars that the Greeks thought looked like a giant hunter with a sword attached to his belt. Other than making a pattern in Earth’s sky, these stars may not be related at all.

Even the closest star is almost unimaginably far away. Because they are so far away, the shapes and positions of the constellations in Earth’s sky change very, very slowly. During one human lifetime, they change hardly at all.

A Long History of Looking to the Stars

The Babylonians lived over 3,000 years ago. They divided the zodiac into 12 equal parts – like cutting a pizza into 12 equal slices. They picked 12 constellations in the zodiac, one for each of the 12 “slices.” So, as Earth orbits the sun, the sun would appear to pass through each of the 12 parts of the zodiac. Since the Babylonians already had a 12-month calendar (based on the phases of the moon), each month got a slice of the zodiac all to itself.

But even according to the Babylonians’ own ancient stories, there were 13 constellations in the zodiac. So they picked one, Ophiuchus, to leave out. Even then, some of the chosen 12 didn’t fit neatly into their assigned slice of the pie and crossed over into the next one.

When the Babylonians first invented the 12 signs of zodiac, a birthday between about July 23 and August 22 meant being born under the constellation Leo. Now, 3,000 years later, the sky has shifted because Earth’s axis (North Pole) doesn’t point in quite the same direction.

The constellations are different sizes and shapes, so the sun spends different lengths of time lined up with each one. The line from Earth through the sun points to Virgo for 45 days, but it points to Scorpius for only 7 days. To make a tidy match with their 12-month calendar, the Babylonians ignored the fact that the sun actually moves through 13 constellations, not 12. Then they assigned each of those 12 constellations equal amounts of time.

So, we didn’t change any zodiac signs…we just did the math.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

-

please-dont-pet-the-okapi liked this · 1 week ago

please-dont-pet-the-okapi liked this · 1 week ago -

artimies6 reblogged this · 1 week ago

artimies6 reblogged this · 1 week ago -

milkygastrobones reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

milkygastrobones reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

leololcat reblogged this · 1 month ago

leololcat reblogged this · 1 month ago -

leololcat liked this · 1 month ago

leololcat liked this · 1 month ago -

scribbly-bear liked this · 1 month ago

scribbly-bear liked this · 1 month ago -

artimies6 liked this · 1 month ago

artimies6 liked this · 1 month ago -

kazeharuhime liked this · 1 month ago

kazeharuhime liked this · 1 month ago -

ellipsis-dotdotdot liked this · 1 month ago

ellipsis-dotdotdot liked this · 1 month ago -

professor-cold-ramen liked this · 1 month ago

professor-cold-ramen liked this · 1 month ago -

chaotic-theatrical-weaver liked this · 1 month ago

chaotic-theatrical-weaver liked this · 1 month ago -

kitty-cat-mint reblogged this · 1 month ago

kitty-cat-mint reblogged this · 1 month ago -

y2kphoenix reblogged this · 1 month ago

y2kphoenix reblogged this · 1 month ago -

thissideofparadise44 liked this · 1 month ago

thissideofparadise44 liked this · 1 month ago -

okaybutwhycantihavemorecats liked this · 1 month ago

okaybutwhycantihavemorecats liked this · 1 month ago -

argen-lobo-ridder liked this · 1 month ago

argen-lobo-ridder liked this · 1 month ago -

tzarina-alexandra reblogged this · 1 month ago

tzarina-alexandra reblogged this · 1 month ago -

tzarina-alexandra liked this · 1 month ago

tzarina-alexandra liked this · 1 month ago -

thepaintdragon liked this · 1 month ago

thepaintdragon liked this · 1 month ago -

ladyofthelands reblogged this · 1 month ago

ladyofthelands reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ladyofthelands liked this · 1 month ago

ladyofthelands liked this · 1 month ago -

soundlessdragon liked this · 1 month ago

soundlessdragon liked this · 1 month ago -

catkin-morgs-kookaburralover reblogged this · 1 month ago

catkin-morgs-kookaburralover reblogged this · 1 month ago -

q587p reblogged this · 1 month ago

q587p reblogged this · 1 month ago -

photonically-unstoppable liked this · 1 month ago

photonically-unstoppable liked this · 1 month ago -

kyungtae-nim liked this · 1 month ago

kyungtae-nim liked this · 1 month ago -

dragononymous liked this · 2 months ago

dragononymous liked this · 2 months ago -

bubblybobbles liked this · 2 months ago

bubblybobbles liked this · 2 months ago -

glasseyekeychain liked this · 2 months ago

glasseyekeychain liked this · 2 months ago -

igneous-rocks17 liked this · 3 months ago

igneous-rocks17 liked this · 3 months ago -

shantalangel reblogged this · 3 months ago

shantalangel reblogged this · 3 months ago -

shantalangel liked this · 3 months ago

shantalangel liked this · 3 months ago -

jthepearlord liked this · 3 months ago

jthepearlord liked this · 3 months ago -

thefuglyducking liked this · 3 months ago

thefuglyducking liked this · 3 months ago -

s-h-y-y-a-n-n-e liked this · 3 months ago

s-h-y-y-a-n-n-e liked this · 3 months ago -

twilight0wanderer liked this · 4 months ago

twilight0wanderer liked this · 4 months ago -

megatonhammer liked this · 4 months ago

megatonhammer liked this · 4 months ago -

a-fire-that-isnt-burning reblogged this · 4 months ago

a-fire-that-isnt-burning reblogged this · 4 months ago -

pretty-sharp-teeth reblogged this · 4 months ago

pretty-sharp-teeth reblogged this · 4 months ago -

pretty-sharp-teeth liked this · 4 months ago

pretty-sharp-teeth liked this · 4 months ago -

vexiad0 liked this · 5 months ago

vexiad0 liked this · 5 months ago -

auroraknux liked this · 5 months ago

auroraknux liked this · 5 months ago -

mocha-coffee-enlivening reblogged this · 5 months ago

mocha-coffee-enlivening reblogged this · 5 months ago -

mocha-coffee-enlivening liked this · 5 months ago

mocha-coffee-enlivening liked this · 5 months ago -

jupitervortexx reblogged this · 5 months ago

jupitervortexx reblogged this · 5 months ago -

thetrashman43 liked this · 5 months ago

thetrashman43 liked this · 5 months ago -

noelle224 reblogged this · 5 months ago

noelle224 reblogged this · 5 months ago -

robin-notabird reblogged this · 5 months ago

robin-notabird reblogged this · 5 months ago -

robin-notabird liked this · 5 months ago

robin-notabird liked this · 5 months ago -

maxboi liked this · 5 months ago

maxboi liked this · 5 months ago