Your gateway to endless inspiration

10things - Blog Posts

A Tour of Storms Across the Solar System

Earth is a dynamic and stormy planet with everything from brief, rumbling thunderstorms to enormous, raging hurricanes, which are some of the most powerful and destructive storms on our world. But other planets also have storm clouds, lightning — even rain, of sorts. Let’s take a tour of some of the unusual storms in our solar system and beyond.

Tune in May 22 at 3 p.m. for more solar system forecasting with NASA Chief Scientist Jim Green during the latest installment of NASA Science Live: https://www.nasa.gov/nasasciencelive.

1. At Mercury: A Chance of Morning Micrometeoroid Showers and Magnetic ‘Tornadoes’

Mercury, the planet nearest the Sun, is scorching hot, with daytime temperatures of more than 800 degrees Fahrenheit (about 450 degrees Celsius). It also has weak gravity — only about 38% of Earth's — making it hard for Mercury to hold on to an atmosphere.

Its barely there atmosphere means Mercury doesn’t have dramatic storms, but it does have a strange "weather" pattern of sorts: it’s blasted with micrometeoroids, or tiny dust particles, usually in the morning. It also has magnetic “tornadoes” — twisted bundles of magnetic fields that connect the planet’s magnetic field to space.

2. At Venus: Earth’s ‘Almost’ Twin is a Hot Mess

Venus is often called Earth's twin because the two planets are similar in size and structure. But Venus is the hottest planet in our solar system, roasting at more than 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius) under a suffocating blanket of sulfuric acid clouds and a crushing atmosphere. Add to that the fact that Venus has lightning, maybe even more than Earth.

In visible light, Venus appears bright yellowish-white because of its clouds. Earlier this year, Japanese researchers found a giant streak-like structure in the clouds based on observations by the Akatsuki spacecraft orbiting Venus.

3. At Earth: Multiple Storm Hazards Likely

Earth has lots of storms, including thunderstorms, blizzards and tornadoes. Tornadoes can pack winds over 300 miles per hour (480 kilometers per hour) and can cause intense localized damage.

But no storms match hurricanes in size and scale of devastation. Hurricanes, also called typhoons or cyclones, can last for days and have strong winds extending outward for 675 miles (1,100 kilometers). They can annihilate coastal areas and cause damage far inland.

4. At Mars: Hazy with a Chance of Dust Storms

Mars is infamous for intense dust storms, including some that grow to encircle the planet. In 2018, a global dust storm blanketed NASA's record-setting Opportunity rover, ending the mission after 15 years on the surface.

Mars has a thin atmosphere of mostly carbon dioxide. To the human eye, the sky would appear hazy and reddish or butterscotch colored because of all the dust suspended in the air.

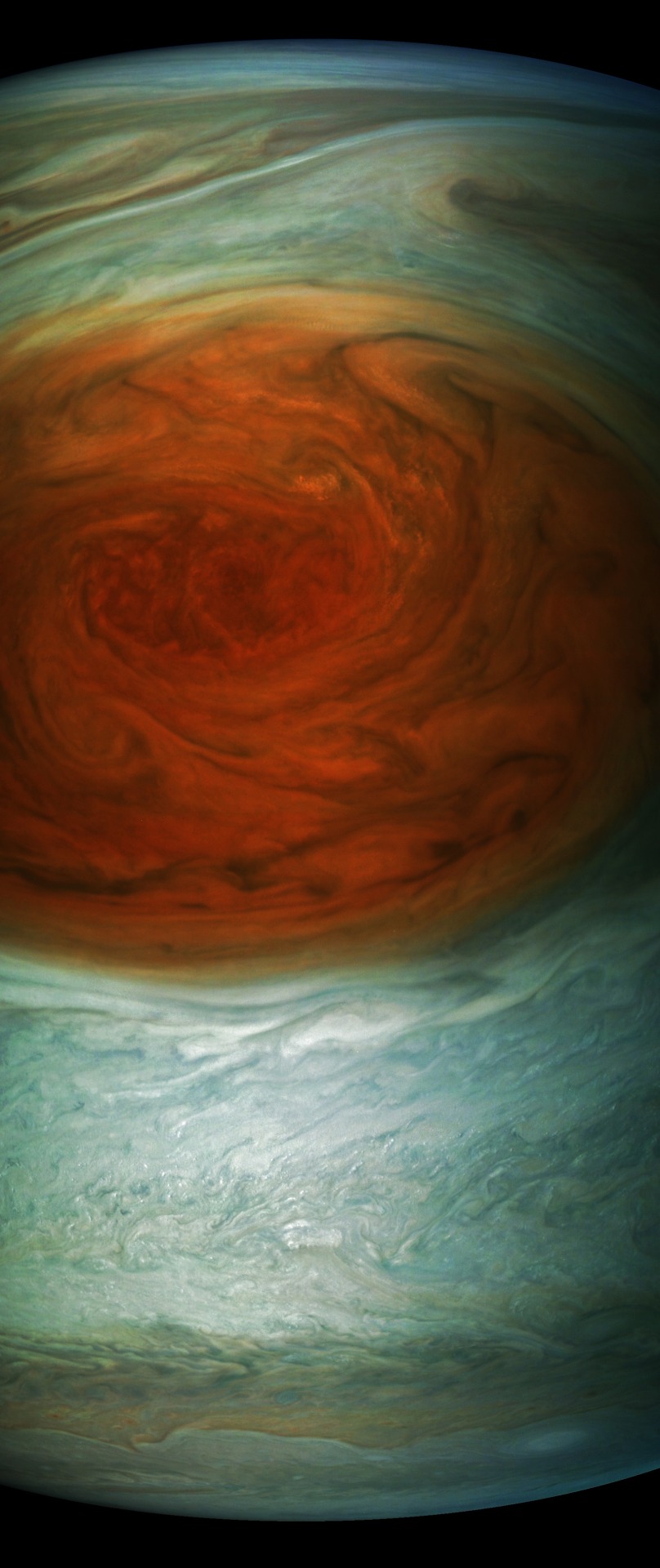

5. At Jupiter: A Shrinking Icon

It’s one of the best-known storms in the solar system: Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. It’s raged for at least 300 years and was once big enough to swallow Earth with room to spare. But it’s been shrinking for a century and a half. Nobody knows for sure, but it's possible the Great Red Spot could eventually disappear.

6. At Saturn: A Storm Chasers Paradise

Saturn has one of the most extraordinary atmospheric features in the solar system: a hexagon-shaped cloud pattern at its north pole. The hexagon is a six-sided jet stream with 200-mile-per-hour winds (about 322 kilometers per hour). Each side is a bit wider than Earth and multiple Earths could fit inside. In the middle of the hexagon is what looks like a cosmic belly button, but it’s actually a huge vortex that looks like a hurricane.

Storm chasers would have a field day on Saturn. Part of the southern hemisphere was dubbed "Storm Alley" by scientists on NASA's Cassini mission because of the frequent storm activity the spacecraft observed there.

7. At Titan: Methane Rain and Dust Storms

Earth isn’t the only world in our solar system with bodies of liquid on its surface. Saturn’s moon Titan has rivers, lakes and large seas. It’s the only other world with a cycle of liquids like Earth’s water cycle, with rain falling from clouds, flowing across the surface, filling lakes and seas and evaporating back into the sky. But on Titan, the rain, rivers and seas are made of methane instead of water.

Data from the Cassini spacecraft also revealed what appear to be giant dust storms in Titan’s equatorial regions, making Titan the third solar system body, in addition to Earth and Mars, where dust storms have been observed.

8. At Uranus: A Polar Storm

Scientists were trying to solve a puzzle about clouds on the ice giant planet: What were they made of? When Voyager 2 flew by in 1986, it spotted few clouds. (This was due in part to the thick haze that envelops the planet, as well as Voyager's cameras not being designed to peer through the haze in infrared light.) But in 2018, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope snapped an image showing a vast, bright, stormy cloud cap across the north pole of Uranus.

9. At Neptune: Methane Clouds

Neptune is our solar system's windiest world. Winds whip clouds of frozen methane across the ice giant planet at speeds of more than 1,200 miles per hour (2,000 kilometers per hour) — about nine times faster than winds on Earth.

Neptune also has huge storm systems. In 1989, NASA’s Voyager 2 spotted two giant storms on Neptune as the spacecraft zipped by the planet. Scientists named the storms “The Great Dark Spot” and “Dark Spot 2.”

10. It’s Not Just Us: Extreme Weather in Another Solar System

Scientists using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope made a global map of the glow from a turbulent planet outside our solar system. The observations show the exoplanet, called WASP-43b, is a world of extremes. It has winds that howl at the speed of sound, from a 3,000-degree-Fahrenheit (1,600-degree-Celsius) day side, to a pitch-black night side where temperatures plunge below 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius).

Discovered in 2011, WASP-43b is located 260 light-years away. The planet is too distant to be photographed, but astronomers detected it by observing dips in the light of its parent star as the planet passes in front of it.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Make Sure You Observe the Moon on October 20

On Saturday, October 20, NASA will host the ninth annual International Observe the Moon Night. One day each year, everyone on Earth is invited to observe and learn about the Moon together, and to celebrate the cultural and personal connections we all have with our nearest celestial neighbor.

There are a number of ways to celebrate. You can attend an event, host your own, or just look up! Here are 10 of our favorite ways to observe the Moon:

1. Look up

Image credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio/Ernie Wright

The simplest way to observe the Moon is simply to look up. The Moon is the brightest object in our night sky, the second brightest in our daytime sky and can be seen from all around the world — from the remote and dark Atacama Desert in Chile to the brightly lit streets of Tokyo. On October 20, the near side of the Moon, or the side facing Earth, will be about 80 percent illuminated, rising in the early evening.

See the Moon phase on October 20 or any other day of the year!

2. Peer through a telescope or binoculars

The Moon and Venus are great targets for binoculars. Image Credit: NASA/Bill Dunford

With some magnification help, you will be able to focus in on specific features on the Moon, like the Sea of Tranquility or the bright Copernicus Crater. Download our Moon maps for some guided observing on Saturday.

3. Photograph the Moon

Image credit: NASA/GSFC/ASU

Our Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has taken more than 20 million images of the Moon, mapping it in stunning detail. You can see featured, captioned images on LRO’s camera website, like the one of Montes Carpatus seen here. And, of course, you can take your own photos from Earth. Check out our tips on photographing the Moon!

4. Take a virtual field trip

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Plan a lunar hike with Moontrek. Moontrek is an interactive Moon map made using NASA data from our lunar spacecraft. Fly anywhere you’d like on the Moon, calculate the distance or the elevation of a mountain to plan your lunar hike, or layer attributes of the lunar surface and temperature. If you have a virtual reality headset, you can experience Moontrek in 3D.

5. Touch the topography

Image credit: NASA GSFC/Jacob Richardson

Observe the Moon through touch! If you have access to a 3D printer, you can peruse our library of 3D models and lunar landscapes. This model of the Apollo 11 landing site created by NASA scientist Jacob Richardson, is derived from LRO’s topographic data. Near the center, you can actually feel a tiny dot where astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left the Lunar Descent Module.

6. Make Moon art

Image credit: LPI/Andy Shaner

Enjoy artwork of the Moon and create your own! For messy fun, lunar crater paintings demonstrate how the lunar surface changes due to consistent meteorite impacts.

7. Relax on your couch

Image credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio/Ernie Wright

There are many movies that feature our nearest neighbor, from A Voyage to the Moon by George Melies, to Apollo 13, to the newly released First Man. You can also spend your evening with our lunar playlist on YouTube or this video gallery, learning about the Moon’s role in eclipses, looking at the Moon phases from the far side, and seeing the latest science portrayed in super high resolution. You’ll impress all of your friends with your knowledge of supermoons.

8. Listen to the Moon

Video credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio/Ernie Wright

Make a playlist of Moon songs. For inspiration, check out this list of lunar tunes. We also recommend LRO’s official music video, The Moon and More, featuring Javier Colon, season 1 winner of NBC’s “The Voice.” Or you can just watch this video featuring “Clair de Lune,” by French composer Claude Debussy, over and over.

9. See the Moon through the eyes of a spacecraft

Image credit: NASA/GSFC/MIT

Visible light is just one tool that we use to explore our universe. Our spacecraft contain many different types of instruments to analyze the Moon’s composition and environment. Review the Moon’s gravity field with data from the GRAIL spacecraft or decipher the maze of this slope map from the laser altimeter onboard LRO. This collection from LRO features images of the Moon’s temperature and topography. You can learn more about our different missions to explore the Moon here.

10. Continue your observations throughout the year

Image credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio/Ernie Wright

An important part of observing the Moon is to see how it changes over time. International Observe the Moon Night is the perfect time to start a Moon journal. See how the shape of the Moon changes over the course of a month, and keep track of where and what time it rises and sets. Observe the Moon all year long with these tools and techniques!

However you choose to celebrate International Observe the Moon Night, we want to hear about it! Register your participation and share your experiences on social media with #ObserveTheMoon or on our Facebook page. Happy observing!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

What's That Space Rock?

The path through the solar system is a rocky road. Asteroids, comets, Kuiper Belt Objects—all kinds of small bodies of rock, metal and ice are in constant motion as they orbit the Sun. But what’s the difference between them, anyway? And why do these miniature worlds fascinate space explorers so much? The answer is profound: they may hold the keys to better understanding where we all come from. Here’s 10 things to know about the solar system this week:

This picture of Eros, the first of an asteroid taken from an orbiting spacecraft, came from our NEAR mission in February 2000. Image credit: NASA/JPL

1. Asteroids

Asteroids are rocky, airless worlds that orbit our Sun. They are remnants left over from the formation of our solar system, ranging in size from the length of a car to about as wide as a large city. Asteroids are diverse in composition; some are metallic while others are rich in carbon, giving them a coal-black color. They can be “rubble piles,” loosely held together by their own gravity, or they can be solid rocks.

Most of the asteroids in our solar system reside in a region called the main asteroid belt. This vast, doughnut-shaped ring between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter contains hundreds of thousands of asteroids, maybe millions. But despite what you see in the movies, there is still a great deal of space between each asteroid. With all due respect to C3PO, the odds of flying through the asteroid belt without colliding with one are actually pretty good.

Other asteroids (and comets) follow different orbits, including some that enter Earth’s neighborhood. These are called near-Earth objects, or NEOs. We can actually keep track of the ones we have discovered and predict where they are headed. The Minor Planet Center (MPC) and Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) do that very thing. Telescopes around the world and in space are used to spot new asteroids and comets, and the MPC and CNEOS, along with international colleagues, calculate where those asteroids and comets are going and determine whether they might pose any impact threat to Earth.

For scientists, asteroids play the role of time capsules from the early solar system, having been preserved in the vacuum of space for billions of years. What’s more, the main asteroid belt may have been a source of water—and organic compounds critical to life—for the inner planets like Earth.

The nucleus of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, as seen in January 2015 by the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft. Image credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

2. Comets

Comets also orbit the Sun, but they are more like snowballs than space rocks. Each comet has a center called a nucleus that contains icy chunks of frozen gases, along with bits of rock and dust. When a comet’s orbit brings it close to the Sun, the comet heats up and spews dust and gases, forming a giant, glowing ball called a coma around its nucleus, along with two tails – one made of dust and the other of excited gas (ions). Driven by a constant flow of particles from the Sun called the solar wind, the tails point away from the Sun, sometimes stretching for millions of miles.

While there are likely billions of comets in the solar system, the current confirmed number is 3,535. Like asteroids, comets are leftover material from the formation of our solar system around 4.6 billion years ago, and they preserve secrets from the earliest days of the Sun’s family. Some of Earth’s water and other chemical constituents could have been delivered by comet impacts.

An artist re-creation of a collision in deep space. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

3. Meteoroids

Meteoroids are fragments and debris in space resulting from collisions among asteroids, comets, moons and planets. They are among the smallest “space rocks.” However, we can actually see them when they streak through our atmosphere in the form of meteors and meteor showers.

This photograph, taken by an astronaut aboard the International Space Station, provides the unusual perspective of looking down on a meteor as it passes through the atmosphere. The image was taken on Aug. 13, 2011, during the Perseid meteor shower that occurs every August. Image credit: NASA

4. Meteors

Meteors are meteoroids that fall through Earth’s atmosphere at extremely high speeds. The pressure and heat they generate as they push through the air causes them to glow and create a streak of light in the sky. Most burn up completely before touching the ground. We often refer to them as “shooting stars.” Meteors may be made mostly of rock, metal or a combination of the two.

Scientists estimate that about 48.5 tons (44,000 kilograms) of meteoritic material falls on Earth each day.

The constellation Orion is framed by two meteors during the Perseid shower on Aug. 12, 2018 in Cedar Breaks National Monument, Utah. Image credit: NASA/Bill Dunford

5. Meteor Showers

Several meteors per hour can usually be seen on any given night. Sometimes the number increases dramatically—these events are termed meteor showers. They occur when Earth passes through trails of particles left by comets. When the particles enter Earth’s atmosphere, they burn up, creating hundreds or even thousands of bright streaks in the sky. We can easily plan when to watch meteor showers because numerous showers happen annually as Earth’s orbit takes it through the same patches of comet debris. This year’s Orionid meteor shower peaks on Oct. 21.

An SUV-sized asteroid, 2008TC#, impacted on Oct. 7, 2008, in the Nubian Desert, Northern Sudan. Dr. Peter Jenniskens, NASA/SETI, joined Muawia Shaddas of the University of Khartoum in leading an expedition on a search for samples. Image credit: NASA/SETI/P. Jenniskens

6. Meteorites

Meteorites are asteroid, comet, moon and planet fragments (meteoroids) that survive the heated journey through Earth’s atmosphere all the way to the ground. Most meteorites found on Earth are pebble to fist size, but some are larger than a building.

Early Earth experienced many large meteorite impacts that caused extensive destruction. Well-documented stories of modern meteorite-caused injury or death are rare. In the first known case of an extraterrestrial object to have injured a human being in the U.S., Ann Hodges of Sylacauga, Alabama, was severely bruised by a 8-pound (3.6-kilogram) stony meteorite that crashed through her roof in November 1954.

The largest object in the asteroid belt is actually a dwarf planet, Ceres. This view comes from our Dawn mission. The color is approximately as it would appear to the eye. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

7. Dwarf Planets

Don’t let the name fool you; despite their small size, dwarf planets are worlds that are just as compelling as their larger siblings. Dwarf planets are defined by astronomers as bodies massive enough to be shaped by gravity into a round or nearly round shape, but they don’t have enough of their own gravitational muscle to clear their path of other objects as they orbit the Sun. In our solar system, dwarf planets are mostly found in the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune; Pluto is the best-known example. But the largest object in the asteroid belt is the dwarf planet Ceres. Like Pluto, Ceres shows signs of active geology, including ice volcanoes.

8. Kuiper Belt Objects

The Kuiper Belt is a disc-shaped region beyond Neptune that extends from about 30 to 55 astronomical units -- that is, 30 to 55 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun. There may be hundreds of thousands of icy bodies and a trillion or more comets in this distant region of our solar system.

An artist's rendition of the New Horizons spacecraft passing by the Kuiper Belt Object MU69 in January 2019. Image credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Besides Pluto, some of the mysterious worlds of the Kuiper Belt include Eris, Sedna, Quaoar, Makemake and Haumea. Like asteroids and comets, Kuiper Belt objects are time capsules, perhaps kept even more pristine in their icy realm.

This chart puts solar system distances in perspective. The scale bar is in astronomical units (AU), with each set distance beyond 1 AU representing 10 times the previous distance. One AU is the distance from the Sun to the Earth, which is about 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers. Neptune, the most distant planet from the Sun, is about 30 AU. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

9. Oort Cloud Objects

The Oort Cloud is a group of icy bodies beginning roughly 186 billion miles (300 billion kilometers) away from the Sun. While the planets of our solar system orbit in a flat plane, the Oort Cloud is believed to be a giant spherical shell surrounding the Sun, planets and Kuiper Belt Objects. It is like a big, thick bubble around our solar system. The Oort Cloud’s icy bodies can be as large as mountains, and sometimes larger.

This dark, cold expanse is by far the solar system’s largest and most distant region. It extends all the way to about 100,000 AU (100,000 times the distance between Earth and the Sun) – a good portion of the way to the next star system. Comets from the Oort Cloud can have orbital periods of thousands or even millions of years. Consider this: At its current speed of about a million miles a day, our Voyager 1 spacecraft won’t reach the Oort Cloud for more than 300 years. It will then take about 30,000 years for the spacecraft to traverse the Oort Cloud, and exit our solar system entirely.

This animation shows our OSIRIS-REx spacecraft collecting a sample of the asteroid Bennu, which it is expected to do in 2020. Image credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

10. The Explorers

Fortunately, even though the Oort Cloud is extremely distant, most of the small bodies we’ve been discussing are more within reach. In fact, NASA and other space agencies have a whole flotilla of robotic spacecraft that are exploring these small worlds up close. Our mechanical emissaries act as our eyes and hands in deep space, searching for whatever clues these time capsules hold.

A partial roster of our current or recent missions to small, rocky destinations includes:

OSIRIS-REx – Now approaching the asteroid Bennu, where it will retrieve a sample in 2020 and return it to the Earth for close scrutiny.

New Horizons – Set to fly close to MU69 or “Ultima Thule,” an object a billion miles past Pluto in the Kuiper Belt on Jan. 1, 2019. When it does, MU69 will become the most distant object humans have ever seen up close.

Psyche – Planned for launch in 2022, the spacecraft will explore a metallic asteroid of the same name, which may be the ejected core of a baby planet that was destroyed long ago.

Lucy – Slated to investigate two separate groups of asteroids, called Trojans, that share the orbit of Jupiter – one group orbits ahead of the planet, while the other orbits behind. Lucy is planned to launch in 2021.

Dawn – Finishing up a successful seven-year mission orbiting planet-like worlds Ceres and Vesta in the asteroid belt.

Plus these missions from other space agencies:

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)’s Hayabusa2– Just landed a series of small probes on the surface of the asteroid Ryugu.

The European Space Agency (ESA)’s Rosetta – Orbited the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and dispatched a lander to its surface.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Did somebody say space laser?

We’re set to launch ICESat-2, our most advanced laser instrument of its kind, into orbit around Earth on Sept. 15. The Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2 will make critical observations of how ice sheets, glaciers and sea ice are changing over time, helping us better understand how those changes affect people where they live. Here’s 10 numbers to know about this mission:

One Space Laser

There’s only one scientific instrument on ICESat-2, but it’s a marvel. The Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or ATLAS, measures height by precisely timing how long it takes individual photons of light from a laser to leave the satellite, bounce off Earth, and return to ICESat-2. Hundreds of people at our Goddard Space Flight Center worked to build this smart-car-sized instrument to exacting requirements so that scientists can measure minute changes in our planet’s ice.

Sea ice is seen in front of Apusiaajik Glacier in Greenland. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Jim Round

Two Types of Ice

Not all ice is the same. Land ice, like the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, or glaciers dotting the Himalayas, builds up as snow falls over centuries and forms compacted layers. When it melts, it can flow into the ocean and raise sea level. Sea ice, on the other hand, forms when ocean water freezes. It can last for years, or a single winter. When sea ice disappears, there is no effect on sea level (think of a melting ice cube in your drink), but it can change climate and weather patterns far beyond the poles.

3-Dimensional Earth

ICESat-2 will measure elevation to see how much glaciers, sea ice and ice sheets are rising or falling. Our fleet of satellites collect detailed images of our planet that show changes to features like ice sheets and forests, and with ICESat-2’s data, scientists can add the third dimension – height – to those portraits of Earth.

Four Seasons, Four Measurements

ICESat-2’s orbit will make 1,387 unique ground tracks around Earth in 91 days – and then start the same ground pattern again at the beginning. This allows the satellite to measure the same ground tracks four times a year and scientists to see how glaciers and other frozen features change with the seasons – including over winter.

532 Nanometer Wavelength

The ATLAS instrument will measure ice with a laser that shines at 532 nanometers – a bright green on the visible spectrum. When these laser photons return to the satellite, they pass through a series of filters that block any light that’s not exactly at this wavelength. This helps the instrument from being swamped with all the other shades of sunlight naturally reflected from Earth.

Six Laser Beams

While the first ICESat satellite (2003-2009) measured ice with a single laser beam, ICESat-2 splits its laser light into six beams – the better to cover more ground (or ice). The arrangement of the beams into three pairs will also allow scientists to assess the slope of the surface they’re measuring.

Seven Kilometers Per Second

ICESat-2 will zoom above the planet at 7 km per second (4.3 miles per second), completing an orbit around Earth in 90 minutes. The orbits have been set to converge at the 88-degree latitude lines around the poles, to focus the data coverage in the region where scientists expect to see the most change.

800-Picosecond Precision

All of those height measurements come from timing the individual laser photons on their 600-mile roundtrip between the satellite and Earth’s surface – a journey that is timed to within 800 picoseconds. That’s a precision of nearly a billionth of a second. Our engineers had to custom build a stopwatch-like device, because no existing timers fit the strict requirements.

Nine Years of Operation IceBridge

As ICESat-2 measures the poles, it adds to our record of ice heights that started with the first ICESat and continued with Operation IceBridge, an airborne mission that has been flying over the Arctic and Antarctic for nine years. The campaign, which bridges the gap between the two satellite missions, has flown since 2009, taking height measurements and documenting the changing ice.

10,000 Pulses a Second

ICESat-2’s laser will fire 10,000 times in one second. The original ICESat fired 40 times a second. More pulses mean more height data. If ICESat-2 flew over a football field, it would take 130 measurements between end zones; its predecessor, on the other hand, would have taken one measurement in each end zone.

And One Bonus Number: 300 Trillion

Each laser pulse ICESat-2 fires contains about 300 trillion photons! Again, the laser instrument is so precise that it can time how long it takes individual photons to return to the satellite to within one billionth of a second.

Learn more about ICESat-2: https://www.nasa.gov/icesat-2

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Why Bennu? 10 Reasons

After traveling for two years and billions of kilometers from Earth, the OSIRIS-REx probe is only a few months away from its destination: the intriguing asteroid Bennu. When it arrives in December, OSIRIS-REx will embark on a nearly two-year investigation of this clump of rock, mapping its terrain and finding a safe and fruitful site from which to collect a sample.

The spacecraft will briefly touch Bennu’s surface around July 2020 to collect at least 60 grams (equal to about 30 sugar packets) of dirt and rocks. It might collect as much as 2,000 grams, which would be the largest sample by far gathered from a space object since the Apollo Moon landings. The spacecraft will then pack the sample into a capsule and travel back to Earth, dropping the capsule into Utah's west desert in 2023, where scientists will be waiting to collect it.

This years-long quest for knowledge thrusts Bennu into the center of one of the most ambitious space missions ever attempted. But the humble rock is but one of about 780,000 known asteroids in our solar system. So why did scientists pick Bennu for this momentous investigation? Here are 10 reasons:

1. It's close to Earth

Unlike most other asteroids that circle the Sun in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, Bennu’s orbit is close in proximity to Earth's, even crossing it. The asteroid makes its closest approach to Earth every 6 years. It also circles the Sun nearly in the same plane as Earth, which made it somewhat easier to achieve the high-energy task of launching the spacecraft out of Earth's plane and into Bennu's. Still, the launch required considerable power, so OSIRIS-REx used Earth’s gravity to boost itself into Bennu’s orbital plane when it passed our planet in September 2017.

2. It's the right size

Asteroids spin on their axes just like Earth does. Small ones, with diameters of 200 meters or less, often spin very fast, up to a few revolutions per minute. This rapid spinning makes it difficult for a spacecraft to match an asteroid's velocity in order to touch down and collect samples. Even worse, the quick spinning has flung loose rocks and soil, material known as "regolith" — the stuff OSIRIS-REx is looking to collect — off the surfaces of small asteroids. Bennu’s size, in contrast, makes it approachable and rich in regolith. It has a diameter of 492 meters, which is a bit larger than the height of the Empire State Building in New York City, and rotating once every 4.3 hours.

3. It's really old

Bennu is a leftover fragment from the tumultuous formation of the solar system. Some of the mineral fragments inside Bennu could be older than the solar system. These microscopic grains of dust could be the same ones that spewed from dying stars and eventually coalesced to make the Sun and its planets nearly 4.6 billion years ago. But pieces of asteroids, called meteorites, have been falling to Earth's surface since the planet formed. So why don't scientists just study those old space rocks? Because astronomers can't tell (with very few exceptions) what kind of objects these meteorites came from, which is important context. Furthermore, these stones, that survive the violent, fiery decent to our planet's surface, get contaminated when they land in the dirt, sand, or snow. Some even get hammered by the elements, like rain and snow, for hundreds or thousands of years. Such events change the chemistry of meteorites, obscuring their ancient records.

4. It's well preserved

Bennu, on the other hand, is a time capsule from the early solar system, having been preserved in the vacuum of space. Although scientists think it broke off a larger asteroid in the asteroid belt in a catastrophic collision between about 1 and 2 billion years ago, and hurtled through space until it got locked into an orbit near Earth's, they don’t expect that these events significantly altered it.

5. It might contain clues to the origin of life

Analyzing a sample from Bennu will help planetary scientists better understand the role asteroids may have played in delivering life-forming compounds to Earth. We know from having studied Bennu through Earth- and space-based telescopes that it is a carbonaceous, or carbon-rich, asteroid. Carbon is the hinge upon which organic molecules hang. Bennu is likely rich in organic molecules, which are made of chains of carbon bonded with atoms of oxygen, hydrogen, and other elements in a chemical recipe that makes all known living things. Besides carbon, Bennu also might have another component important to life: water, which is trapped in the minerals that make up the asteroid.

6. It contains valuable materials

Besides teaching us about our cosmic past, exploring Bennu close-up will help humans plan for the future. Asteroids are rich in natural resources, such as iron and aluminum, and precious metals, such as platinum. For this reason, some companies, and even countries, are building technologies that will one day allow us to extract those materials. More importantly, asteroids like Bennu are key to future, deep-space travel. If humans can learn how to extract the abundant hydrogen and oxygen from the water locked up in an asteroid’s minerals, they could make rocket fuel. Thus, asteroids could one day serve as fuel stations for robotic or human missions to Mars and beyond. Learning how to maneuver around an object like Bennu, and about its chemical and physical properties, will help future prospectors.

7. It will help us better understand other asteroids

Astronomers have studied Bennu from Earth since it was discovered in 1999. As a result, they think they know a lot about the asteroid's physical and chemical properties. Their knowledge is based not only on looking at the asteroid, but also studying meteorites found on Earth, and filling in gaps in observable knowledge with predictions derived from theoretical models. Thanks to the detailed information that will be gleaned from OSIRIS-REx, scientists now will be able to check whether their predictions about Bennu are correct. This work will help verify or refine telescopic observations and models that attempt to reveal the nature of other asteroids in our solar system.

8. It will help us better understand a quirky solar force ...

Astronomers have calculated that Bennu’s orbit has drifted about 280 meters (0.18 miles) per year toward the Sun since it was discovered. This could be because of a phenomenon called the Yarkovsky effect, a process whereby sunlight warms one side of a small, dark asteroid and then radiates as heat off the asteroid as it rotates. The heat energy thrusts an asteroid either away from the Sun, if it has a prograde spin like Earth, which means it spins in the same direction as its orbit, or toward the Sun in the case of Bennu, which spins in the opposite direction of its orbit. OSIRIS-REx will measure the Yarkovsky effect from close-up to help scientists predict the movement of Bennu and other asteroids. Already, measurements of how this force impacted Bennu over time have revealed that it likely pushed it to our corner of the solar system from the asteroid belt.

9. ... and to keep asteroids at bay

One reason scientists are eager to predict the directions asteroids are drifting is to know when they're coming too-close-for-comfort to Earth. By taking the Yarkovsky effect into account, they’ve estimated that Bennu could pass closer to Earth than the Moon is in 2135, and possibly even closer between 2175 and 2195. Although Bennu is unlikely to hit Earth at that time, our descendants can use the data from OSIRIS-REx to determine how best to deflect any threatening asteroids that are found, perhaps even by using the Yarkovsky effect to their advantage.

10. It's a gift that will keep on giving

Samples of Bennu will return to Earth on September 24, 2023. OSIRIS-REx scientists will study a quarter of the regolith. The rest will be made available to scientists around the globe, and also saved for those not yet born, using techniques not yet invented, to answer questions not yet asked.

Read the web version of this week’s “Solar System: 10 Things to Know” article HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Solar System 10 Things: Two Years of Juno at Jupiter

Our Juno mission arrived at the King of Planets in July 2016. The intrepid robotic explorer has been revealing Jupiter's secrets ever since.

Here are 10 historic Juno mission highlights:

1. Arrival at a Colossus

After an odyssey of almost five years and 1.7 billion miles (2.7 billion kilometers), our Juno spacecraft fired its main engine to enter orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Juno, with its suite of nine science instruments, was the first spacecraft to orbit the giant planet since the Galileo mission in the 1990s. It would be the first mission to make repeated excursions close to the cloud tops, deep inside the planet’s powerful radiation belts.

2. Science, Meet Art

Juno carries a color camera called JunoCam. In a remarkable first for a deep space mission, the Juno team reached out to the general public not only to help plan which pictures JunoCam would take, but also to process and enhance the resulting visual data. The results include some of the most beautiful images in the history of space exploration.

3. A Whole New Jupiter

It didn’t take long for Juno—and the science teams who hungrily consumed the data it sent home—to turn theories about how Jupiter works inside out. Among the early findings: Jupiter's poles are covered in Earth-sized swirling storms that are densely clustered and rubbing together. Jupiter's iconic belts and zones were surprising, with the belt near the equator penetrating far beneath the clouds, and the belts and zones at other latitudes seeming to evolve to other structures below the surface.

4. The Ultimate Classroom

The Goldstone Apple Valley Radio Telescope (GAVRT) project, a collaboration among NASA, JPL and the Lewis Center for Educational Research, lets students do real science with a large radio telescope. GAVRT data includes Jupiter observations relevant to Juno, and Juno scientists collaborate with the students and their teachers.

5. Spotting the Spot

Measuring in at 10,159 miles (16,350 kilometers) in width (as of April 3, 2017) Jupiter's Great Red Spot is 1.3 times as wide as Earth. The storm has been monitored since 1830 and has possibly existed for more than 350 years. In modern times, the Great Red Spot has appeared to be shrinking. In July 2017, Juno passed directly over the spot, and JunoCam images revealed a tangle of dark, veinous clouds weaving their way through a massive crimson oval.

“For hundreds of years scientists have been observing, wondering and theorizing about Jupiter’s Great Red Spot,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Now we have the best pictures ever of this iconic storm. It will take us some time to analyze all the data from not only JunoCam, but Juno’s eight science instruments, to shed some new light on the past, present and future of the Great Red Spot.”

6. Beauty Runs Deep

Data collected by the Juno spacecraft during its first pass over Jupiter's Great Red Spot in July 2017 indicate that this iconic feature penetrates well below the clouds. The solar system's most famous storm appears to have roots that penetrate about 200 miles (300 kilometers) into the planet's atmosphere.

7. Powerful Auroras, Powerful Mysteries

Scientists on the Juno mission observed massive amounts of energy swirling over Jupiter’s polar regions that contribute to the giant planet’s powerful auroras – only not in ways the researchers expected. Examining data collected by the ultraviolet spectrograph and energetic-particle detector instruments aboard Juno, scientists observed signatures of powerful electric potentials, aligned with Jupiter’s magnetic field, that accelerate electrons toward the Jovian atmosphere at energies up to 400,000 electron volts. This is 10 to 30 times higher than the largest such auroral potentials observed at Earth.

Jupiter has the most powerful auroras in the solar system, so the team was not surprised that electric potentials play a role in their generation. What puzzled the researchers is that despite the magnitudes of these potentials at Jupiter, they are observed only sometimes and are not the source of the most intense auroras, as they are at Earth.

8. Heat from Within

Juno scientists shared a 3D infrared movie depicting densely packed cyclones and anticyclones that permeate the planet’s polar regions, and the first detailed view of a dynamo, or engine, powering the magnetic field for any planet beyond Earth (video above). Juno mission scientists took data collected by the spacecraft’s Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument and generated a 3D fly-around of the Jovian world’s north pole.

Imaging in the infrared part of the spectrum, JIRAM captures light emerging from deep inside Jupiter equally well, night or day. The instrument probes the weather layer down to 30 to 45 miles (50 to 70 kilometers) below Jupiter's cloud tops.

9. A Highly Charged Atmosphere

Powerful bolts of lightning light up Jupiter’s clouds. In some ways its lightning is just like what we’re used to on Earth. In other ways,it’s very different. For example, most of Earth’s lightning strikes near the equator; on Jupiter, it’s mostly around the poles.

10. Extra Innings

In June, we approved an update to Juno’s science operations until July 2021. This provides for an additional 41 months in orbit around. Juno is in 53-day orbits rather than 14-day orbits as initially planned because of a concern about valves on the spacecraft’s fuel system. This longer orbit means that it will take more time to collect the needed science data, but an independent panel of experts confirmed that Juno is on track to achieve its science objectives and is already returning spectacular results. The spacecraft and all its instruments are healthy and operating nominally.

Read the full web version of this week’s ‘Solar System: 10 Things to Know’ article HERE.

For regular updates, follow NASA Solar System on Twitter and Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Solar System: 10 Things to Know This Week

Week of March 5: Great Shots Inspiring views of our solar system and beyond

1-Mars-By-Numbers

“The first TV image of Mars, hand colored strip-by-strip, from Mariner 4 in 1965. The completed image was framed and presented to JPL director, William H. Pickering. Truly a labor of love for science!” -Kristen Erickson, NASA Science Engagement and Partnerships Director

2-Night Life

“There are so many stories to this image. It is a global image, but relates to an individual in one glance. There are stories on social, economic, population, energy, pollution, human migration, technology meets science, enable global information, etc., that we can all communicate with similar interests under one image.” -Winnie Humberson, NASA Earth Science Outreach Manager

3-Pale Blue Dot

“Whenever I see this picture, I wonder...if another species saw this blue dot what would they say and would they want to discover what goes on there...which is both good and bad. However, it would not make a difference within the eternity of space—we’re so insignificant...in essence just dust in the galactic wind—one day gone forever.”

-Dwayne Brown, NASA Senior Communications Official

4-Grand Central

“I observed the Galactic Center with several X-ray telescopes before Chandra, including the Einstein Observatory and ROSAT. But the Chandra image looks nothing like those earlier images, and it reminded me how complex the universe really is. Also I love the colors.” -Paul Hertz, Director, NASA Astrophysics Division

5-Far Side Photobomb

“This image from the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite captured a unique view of the Moon as it moved in front of the sunlit side of Earth in 2015. It shows a view of the farside of the Moon, which faces the Sun, that is never directly visible to us here on Earth. I found this perspective profoundly moving and only through our satellite views could this have been shared.” -Michael Freilich, Director NASA Earth Science Division

6-”Shocking, Exciting and Wonderful”

“Pluto was so unlike anything I could imagine based on my knowledge of the Solar System. It showed me how much about the outer solar system we didn’t know. Truly shocking, exciting and wonderful all at the same time.” -Jim Green, Director, NASA Planetary Science Division

7-Slices of the Sun

“This is an awesome image of the Sun through the Solar Dynamic Observatory’s many filters. It is one of my favorites.” - Peg Luce, Director, NASA Heliophysics Division (Acting)

8-Pluto’s Cold, Cold Heart

“This high-resolution, false color image of Pluto is my favorite. The New Horizons flyby of Pluto on July 14, 2015 capped humanity’s initial reconnaissance of every major body in the solar system. To think that all of this happened within our lifetime! It’s a reminder of how privileged we are to be alive and working at NASA during this historic era of space exploration.” - Laurie Cantillo, NASA Planetary Science Public Affairs Officer

9-Family Portrait

“The Solar System family portrait, because it is a symbol what NASA exploration is really about: Seeing our world in a new and bigger way.” - Thomas H. Zurbuchen, Associate Administrator, NASA Science Mission Directorate

10-Share Your Favorite Space Shots

Tag @NASASolarSystem on your favorite social media platform with a link to your favorite image and few words about why it makes your heart thump.

Check out the full version of this article HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Solar System: 10 Things to Know This Week

Pioneer Days

Someone’s got to be first. In space, the first explorers beyond Mars were Pioneers 10 and 11, twin robots who charted the course to the cosmos.

1-Before Voyager

Voyager, with its outer solar system tour and interstellar observations, is often credited as the greatest robotic space mission. But today we remember the plucky Pioneers, the spacecraft that proved Voyager’s epic mission was possible.

2-Where No One Had Gone Before

Forty-five years ago this week, scientists still weren’t sure how hard it would be to navigate the main asteroid belt, a massive field of rocky debris between Mars and Jupiter. Pioneer 10 helped them work that out, emerging from first the first six-month crossing in February 1973. Pioneer 10 logged a few meteoroid hits (fewer than expected) and taught engineers new tricks for navigating farther and farther beyond Earth.

3-Trailblazer No. 2

Pioneer 11 was a backup spacecraft launched in 1973 after Pioneer 10 cleared the asteroid belt. The new mission provided a second close look at Jupiter, the first close-up views of Saturn and also gave Voyager engineers plotting an epic multi-planet tour of the outer planets a chance to practice the art of interplanetary navigation.

4-First to Jupiter

Three-hundred and sixty-three years after humankind first looked at Jupiter through a telescope, Pioneer 10 became the first human-made visitor to the Jovian system in December 1973. The spacecraft spacecraft snapped about 300 photos during a flyby that brought it within 81,000 miles (about 130,000 kilometers) of the giant planet’s cloud tops.

5-Pioneer Family

Pioneer began as a Moon program in the 1950s and evolved into increasingly more complicated spacecraft, including a Pioneer Venus mission that delivered a series of probes to explore deep into the mysterious toxic clouds of Venus. A family portrait (above) showing (from left to right) Pioneers 6-9, 10 and 11 and the Pioneer Venus Orbiter and Multiprobe series. Image date: March 11, 1982.

6-A Pioneer and a Pioneer

Classic rock has Van Halen, we have Van Allen. With credits from Explorer 1 to Pioneer 11, James Van Allen was a rock star in the emerging world of planetary exploration. Van Allen (1914-2006) is credited with the first scientific discovery in outer space and was a fixture in the Pioneer program. Van Allen was a key part of the team from the early attempts to explore the Moon (he’s pictured here with Pioneer 4) to the more evolved science platforms aboard Pioneers 10 and 11.

7-The Farthest...For a While

For more than 25 years, Pioneer 10 was the most distant human-made object, breaking records by crossing the asteroid belt, the orbit of Jupiter and eventually even the orbit of Pluto. Voyager 1, moving even faster, claimed the most distant title in February 1998 and still holds that crown.

8-Last Contact

We last heard from Pioneer 10 on Jan. 23, 2003. Engineers felt its power source was depleted and no further contact should be expected. We tried again in 2006, but had no luck. The last transmission from Pioneer 11 was received in September 1995. Both missions were planned to last about two years.

9-Galactic Ghost Ships

Pioneers 10 and 11 are two of five spacecraft with sufficient velocity to escape our solar system and travel into interstellar space. The other three—Voyagers 1 and 2 and New Horizons—are still actively talking to Earth. The twin Pioneers are now silent. Pioneer 10 is heading generally for the red star Aldebaran, which forms the eye of Taurus (The Bull). It will take Pioneer over 2 million years to reach it. Pioneer 11 is headed toward the constellation of Aquila (The Eagle) and will pass nearby in about 4 million years.

10-The Original Message to the Cosmos

Years before Voyager’s famed Golden Record, Pioneers 10 and 11 carried the original message from Earth to the cosmos. Like Voyager’s record, the Pioneer plaque was the brainchild of Carl Sagan who wanted any alien civilization who might encounter the craft to know who made it and how to contact them. The plaques give our location in the galaxy and depicts a man and woman drawn in relation to the spacecraft.

Read the full version of this week’s 10 Things article HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.