Your gateway to endless inspiration

Exoplanets - Blog Posts

Love Letters from Space

Love is in the air, and it’s out in space too! The universe is full of amazing chemistry, cosmic couples held together by gravitational attraction, and stars pulsing like beating hearts.

Celestial objects send out messages we can detect if we know how to listen for them. Our upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will help us scour the skies for all kinds of star-crossed signals.

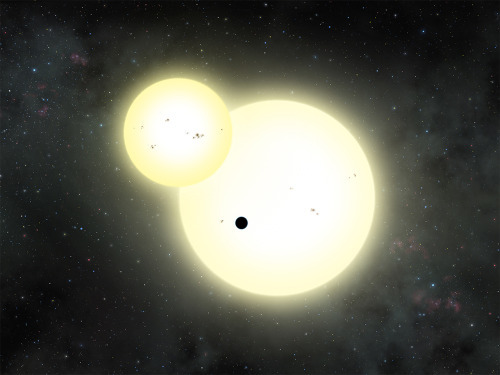

Celestial Conversation Hearts

Communication is key for any relationship – including our relationship with space. Different telescopes are tuned to pick up different messages from across the universe, and combining them helps us learn even more. Roman is designed to see some visible light – the type of light our eyes can see, featured in the photo above from a ground-based telescope – in addition to longer wavelengths, called infrared. That will help us peer through clouds of dust and across immense stretches of space.

Other telescopes can see different types of light, and some detectors can even help us study cosmic rays, ghostly neutrinos, and ripples in space called gravitational waves.

Intergalactic Hugs

This visible and near-infrared image from the Hubble Space Telescope captures two hearts locked in a cosmic embrace. Known as the Antennae Galaxies, this pair’s love burns bright. The two spiral galaxies are merging together, igniting the birth of brand new baby stars.

Stellar nurseries are often very dusty places, which can make it hard to tell what’s going on. But since Roman can peer through dust, it will help us see stars in their infancy. And Roman’s large view of space coupled with its sharp, deep imaging will help us study how galaxy mergers have evolved since the early universe.

Cosmic Chemistry

Those stars are destined to create new chemistry, forging elements and scattering them into space as they live, die, and merge together. Roman will help us understand the cosmic era when stars first began forming. The mission will help scientists learn more about how elements were created and distributed throughout galaxies.

Did you know that U and I (uranium and iodine) were both made from merging neutron stars? Speaking of which…

Fatal Attraction

When two neutron stars come together in a marriage of sorts, it creates some spectacular fireworks! While they start out as stellar sweethearts, these and some other types of cosmic couples are fated for devastating breakups.

When a white dwarf – the leftover core from a Sun-like star that ran out of fuel – steals material from its companion, it can throw everything off balance and lead to a cataclysmic explosion. Studying these outbursts, called type Ia supernovae, led to the discovery that the expansion of the universe is speeding up. Roman will scan the skies for these exploding stars to help us figure out what’s causing the expansion to accelerate – a mystery known as dark energy.

Going Solo

Plenty of things in our galaxy are single, including hundreds of millions of stellar-mass black holes and trillions of “rogue” planets. These objects are effectively invisible – dark objects lost in the inky void of space – but Roman will see them thanks to wrinkles in space-time.

Anything with mass warps the fabric of space-time. So when an intervening object nearly aligns with a background star from our vantage point, light from the star curves as it travels through the warped space-time around the nearer object. The object acts like a natural lens, focusing and amplifying the background star’s light.

Thanks to this observational effect, which makes stars appear to temporarily pulse brighter, Roman will reveal all kinds of things we’d never be able to see otherwise.

Roman is nearly ready to set its sights on so many celestial spectacles. Follow along with the mission’s build progress in this interactive virtual tour of the observatory, and check out these space-themed Valentine’s Day cards.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

A simulated image of NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope’s future observations toward the center of our galaxy, spanning less than 1 percent of the total area of Roman’s Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey. The simulated stars were drawn from the Besançon Galactic Model.

Exploring the Changing Universe with the Roman Space Telescope

The view from your backyard might paint the universe as an unchanging realm, where only twinkling stars and nearby objects, like satellites and meteors, stray from the apparent constancy. But stargazing through NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will offer a front row seat to a dazzling display of cosmic fireworks sparkling across the sky.

Roman will view extremely faint infrared light, which has longer wavelengths than our eyes can see. Two of the mission’s core observing programs will monitor specific patches of the sky. Stitching the results together like stop-motion animation will create movies that reveal changing objects and fleeting events that would otherwise be hidden from our view.

Watch this video to learn about time-domain astronomy and how time will be a key element in NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope’s galactic bulge survey. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

This type of science, called time-domain astronomy, is difficult for telescopes that have smaller views of space. Roman’s large field of view will help us see huge swaths of the universe. Instead of always looking at specific things and events astronomers have already identified, Roman will be able to repeatedly observe large areas of the sky to catch phenomena scientists can't predict. Then astronomers can find things no one knew were there!

One of Roman’s main surveys, the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey, will monitor hundreds of millions of stars toward the center of our Milky Way galaxy. Astronomers will see many of the stars appear to flash or flicker over time.

This animation illustrates the concept of gravitational microlensing. When one star in the sky appears to pass nearly in front of another, the light rays of the background source star are bent due to the warped space-time around the foreground star. The closer star is then a virtual magnifying glass, amplifying the brightness of the background source star, so we refer to the foreground star as the lens star. If the lens star harbors a planetary system, then those planets can also act as lenses, each one producing a short change in the brightness of the source. Thus, we discover the presence of each exoplanet, and measure its mass and how far it is from its star. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

That can happen when something like a star or planet moves in front of a background star from our point of view. Because anything with mass warps the fabric of space-time, light from the distant star bends around the nearer object as it passes by. That makes the nearer object act as a natural magnifying glass, creating a temporary spike in the brightness of the background star’s light. That signal lets astronomers know there’s an intervening object, even if they can’t see it directly.

This artist’s concept shows the region of the Milky Way NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope’s Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey will cover – relatively uncharted territory when it comes to planet-finding. That’s important because the way planets form and evolve may be different depending on where in the galaxy they’re located. Our solar system is situated near the outskirts of the Milky Way, about halfway out on one of the galaxy’s spiral arms. A recent Kepler Space Telescope study showed that stars on the fringes of the Milky Way possess fewer of the most common planet types that have been detected so far. Roman will search in the opposite direction, toward the center of the galaxy, and could find differences in that galactic neighborhood, too.

Using this method, called microlensing, Roman will likely set a new record for the farthest-known exoplanet. That would offer a glimpse of a different galactic neighborhood that could be home to worlds quite unlike the more than 5,500 that are currently known. Roman’s microlensing observations will also find starless planets, black holes, neutron stars, and more!

This animation shows a planet crossing in front of, or transiting, its host star and the corresponding light curve astronomers would see. Using this technique, scientists anticipate NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope could find 100,000 new worlds. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Chris Smith (USRA/GESTAR)

Stars Roman sees may also appear to flicker when a planet crosses in front of, or transits, its host star as it orbits. Roman could find 100,000 planets this way! Small icy objects that haunt the outskirts of our own solar system, known as Kuiper belt objects, may occasionally pass in front of faraway stars Roman sees, too. Astronomers will be able to see how much water the Kuiper belt objects have because the ice absorbs specific wavelengths of infrared light, providing a “fingerprint” of its presence. This will give us a window into our solar system’s early days.

This animation visualizes a type Ia supernova.

Roman’s High Latitude Time-Domain Survey will look beyond our galaxy to hunt for type Ia supernovas. These exploding stars originate from some binary star systems that contain at least one white dwarf – the small, hot core remnant of a Sun-like star. In some cases, the dwarf may siphon material from its companion. This triggers a runaway reaction that ultimately detonates the thief once it reaches a specific point where it has gained so much mass that it becomes unstable.

NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will see thousands of exploding stars called supernovae across vast stretches of time and space. Using these observations, astronomers aim to shine a light on several cosmic mysteries, providing a window onto the universe’s distant past. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Since these rare explosions each peak at a similar, known intrinsic brightness, astronomers can use them to determine how far away they are by simply measuring how bright they appear. Astronomers will use Roman to study the light of these supernovas to find out how quickly they appear to be moving away from us.

By comparing how fast they’re receding at different distances, scientists can trace cosmic expansion over time. This will help us understand whether and how dark energy – the unexplained pressure thought to speed up the universe’s expansion – has changed throughout the history of the universe.

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will survey the same areas of the sky every few days. Researchers will mine this data to identify kilonovas – explosions that happen when two neutron stars or a neutron star and a black hole collide and merge. When these collisions happen, a fraction of the resulting debris is ejected as jets, which move near the speed of light. The remaining debris produces hot, glowing, neutron-rich clouds that forge heavy elements, like gold and platinum. Roman’s extensive data will help astronomers better identify how often these events occur, how much energy they give off, and how near or far they are.

And since this survey will repeatedly observe the same large vista of space, scientists will also see sporadic events like neutron stars colliding and stars being swept into black holes. Roman could even find new types of objects and events that astronomers have never seen before!

Learn more about the exciting science Roman will investigate on X and Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Black Hole Friday Deals!

Get these deals before they are sucked into a black hole and gone forever! This “Black Hole Friday,” we have some cosmic savings that are sure to be out of this world.

Your classic black holes — the ultimate storage solution.

Galactic 5-for-1 special! Learn more about Stephan’s Quintet.

Limited-time offer game DLC! Try your hand at the Roman Space Observer Video Game, Black Hole edition, available this weekend only.

Standard candles: Exploding stars that are reliably bright. Multi-functional — can be used to measure distances in space!

Feed the black hole in your stomach. Spaghettification’s on the menu.

Act quickly before the stars in this widow system are gone!

Add some planets to your solar system! Grab our Exoplanet Bundle.

Get ready to ride this (gravitational) wave before this Black Hole Merger ends!

Be the center of attention in this stylish accretion disk skirt. Made of 100% recycled cosmic material.

Should you ever travel to a black hole? No. But if you do, here’s a free guide to make your trip as safe* as possible. *Note: black holes are never safe.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Hot New Planetary System Just Dropped.

We hope you like your planetary systems extra spicy. 🔥

A new system of seven sizzling planets has been discovered using data from our retired Kepler space telescope.

Named Kepler-385, it’s part of a new catalog of planet candidates and multi-planet systems discovered using Kepler.

The discovery helps illustrate that multi-planetary systems have more circular orbits around the host star than systems with only one or two planets.

Our Kepler mission is responsible for the discovery of the most known exoplanets to date. The space telescope’s observations ended in 2018, but its data continues to paint a more detailed picture of our galaxy today.

Here are a few more things to know about Kepler-385:

All seven planets are between the size of Earth and Neptune.

Its star is 10% larger and 5% hotter than our Sun.

This system is one of over 700 that Kepler’s data has revealed.

The planets’ orbits have been represented in sound.

Now that you’ve heard a little about this planetary system, get acquainted with more exoplanets and why we want to explore them.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

5 Years, 8 Discoveries: NASA Exoplanet Explorer Sees Dancing Stars & a Star-Shredding Black Hole

This all-sky mosaic was constructed from 912 Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) images. Prominent features include the Milky Way, a glowing arc that represents the bright central plane of our galaxy, and the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds – satellite galaxies of our own located, respectively, 160,000 and 200,000 light-years away. In the northern sky, look for the small, oblong shape of the Andromeda galaxy (M 31), the closest big spiral galaxy, located 2.5 million light-years away. The black regions are areas of sky that TESS didn’t image. Credit: NASA/MIT/TESS and Ethan Kruse (University of Maryland College Park)

On April 18, 2018, we launched the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, better known as TESS. It was designed to search for planets beyond our solar system – exoplanets – and to discover worlds for our James Webb Space Telescope, which launched three years later, to further explore. TESS images sections of sky, one hemisphere at a time. When we put all the images together, we get a great look at Earth’s sky!

In its five years in space, TESS has discovered 326 planets and more than 4,300 planet candidates. Along the way, the spacecraft has observed a plethora of other objects in space, including watching as a black hole devoured a star and seeing six stars dancing in space. Here are some notable results from TESS so far:

During its first five years in space, our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite has discovered exoplanets and identified worlds that can be further explored by the James Webb Space Telescope. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

1. TESS’ first discovery was a world called Pi Mensae c. It orbits the star Pi Mensae, about 60 light-years away from Earth and visible to the unaided eye in the Southern Hemisphere. This discovery kicked off NASA's new era of planet hunting.

2. Studying planets often helps us learn about stars too! Data from TESS & Spitzer helped scientists detect a planet around the young, flaring star AU Mic, providing a unique way to study how planets form, evolve, and interact with active stars.

Located less than 32 light-years from Earth, AU Microscopii is among the youngest planetary systems ever observed by astronomers, and its star throws vicious temper tantrums. This devilish young system holds planet AU Mic b captive inside a looming disk of ghostly dust and ceaselessly torments it with deadly blasts of X-rays and other radiation, thwarting any chance of life… as we know it! Beware! There is no escaping the stellar fury of this system. The monstrous flares of AU Mic will have you begging for eternal darkness. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

3. In addition to finding exoplanets on its own, TESS serves as a pathfinder for the James Webb Space Telescope. TESS discovered the rocky world LHS 3844 b, but Webb will tell us more about its composition. Our telescopes, much like our scientists, work together.

4. Though TESS may be a planet-hunter, it also helps us study black holes! In 2019, TESS saw a ‘‘tidal disruption event,’’ otherwise known as a black hole shredding a star.

When a star strays too close to a black hole, intense tides break it apart into a stream of gas. The tail of the stream escapes the system, while the rest of it swings back around, surrounding the black hole with a disk of debris. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

5. In 2020, TESS discovered its first Earth-size world in the habitable zone of its star – the distance from a star at which liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface. Earlier this year, a second rocky planet was discovered in the system.

You can see the exoplanets that orbit the star TOI 700 moving within two marked habitable zones, a conservative habitable zone, and an optimistic habitable zone. Planet d orbits within the conservative habitable zone, while planet e moves within an optimistic habitable zone, the range of distances from a star where liquid surface water could be present at some point in a planet’s history. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

6. Astronomers used TESS to find a six-star system where all stars undergo eclipses. Three binary pairs orbit each other, and, in turn, the pairs are engaged in an elaborate gravitational dance in a cosmic ballroom 1,900 light-years away in the constellation Eridanus.

7. Thanks to TESS, we learned that Delta Scuti stars pulse to the beat of their own drummer. Most seem to oscillate randomly, but we now know HD 31901 taps out a beat that merges 55 pulsation patterns.

Sound waves bouncing around inside a star cause it to expand and contract, which results in detectable brightness changes. This animation depicts one type of Delta Scuti pulsation — called a radial mode — that is driven by waves (blue arrows) traveling between the star's core and surface. In reality, a star may pulsate in many different modes, creating complicated patterns that enable scientists to learn about its interior. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

8. Last is a galaxy that flares like clockwork! With TESS and Swift, astronomers identified the most predictably and frequently flaring active galaxy yet. ASASSN-14ko, which is 570 million light-years away, brightens every 114 days!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

12 Great Gifts from Astronomy

This is a season where our thoughts turn to others and many exchange gifts with friends and family. For astronomers, our universe is the gift that keeps on giving. We’ve learned so much about it, but every question we answer leads to new things we want to know. Stars, galaxies, planets, black holes … there are endless wonders to study.

In honor of this time of year, let’s count our way through some of our favorite gifts from astronomy.

Our first astronomical gift is … one planet Earth

So far, there is only one planet that we’ve found that has everything needed to support life as we know it — Earth. Even though we’ve discovered over 5,200 planets outside our solar system, none are quite like home. But the search continues with the help of missions like our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). And even you (yes, you!) can help in the search with citizen science programs like Planet Hunters TESS and Backyard Worlds.

Our second astronomical gift is … two giant bubbles

Astronomers found out that our Milky Way galaxy is blowing bubbles — two of them! Each bubble is about 25,000 light-years tall and glows in gamma rays. Scientists using data from our Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope discovered these structures in 2010, and we're still learning about them.

Our third astronomical gift is … three types of black holes

Most black holes fit into two size categories: stellar-mass goes up to hundreds of Suns, and supermassive starts at hundreds of thousands of Suns. But what happens between those two? Where are the midsize ones? With the help of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, scientists found the best evidence yet for that third, in between type that we call intermediate-mass black holes. The masses of these black holes should range from around a hundred to hundreds of thousands of times the Sun’s mass. The hunt continues for these elusive black holes.

Our fourth and fifth astronomical gifts are … Stephan’s Quintet

When looking at this stunning image of Stephan’s Quintet from our James Webb Space Telescope, it seems like five galaxies are hanging around one another — but did you know that one of the galaxies is much closer than the others? Four of the five galaxies are hanging out together about 290 million light-years away, but the fifth and leftmost galaxy in the image below — called NGC 7320 — is actually closer to Earth at just 40 million light-years away.

Our sixth astronomical gift is … an eclipsing six-star system

Astronomers found a six-star system where all of the stars undergo eclipses, using data from our TESS mission, a supercomputer, and automated eclipse-identifying software. The system, called TYC 7037-89-1, is located 1,900 light-years away in the constellation Eridanus and the first of its kind we’ve found.

Our seventh astronomical gift is … seven Earth-sized planets

In 2017, our now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope helped find seven Earth-size planets around TRAPPIST-1. It remains the largest batch of Earth-size worlds found around a single star and the most rocky planets found in one star’s habitable zone, the range of distances where conditions may be just right to allow the presence of liquid water on a planet’s surface.

Further research has helped us understand the planets’ densities, atmospheres, and more!

Our eighth astronomical gift is … an (almost) eight-foot mirror

The primary mirror on our Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is approximately eight feet in diameter, similar to our Hubble Space Telescope. But Roman can survey large regions of the sky over 1,000 times faster, allowing it to hunt for thousands of exoplanets and measure light from a billion galaxies.

Our ninth astronomical gift is … a kilonova nine days later

In 2017, the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and European Gravitational Observatory’s Virgo detected gravitational waves from a pair of colliding neutron stars. Less than two seconds later, our telescopes detected a burst of gamma rays from the same event. It was the first time light and gravitational waves were seen from the same cosmic source. But then nine days later, astronomers saw X-ray light produced in jets in the collision’s aftermath. This later emission is called a kilonova, and it helped astronomers understand what the slower-moving material is made of.

Our tenth astronomical gift is … NuSTAR’s ten-meter-long mast

Our NuSTAR X-ray observatory is the first space telescope able to focus on high-energy X-rays. Its ten-meter-long (33 foot) mast, which deployed shortly after launch, puts NuSTAR’s detectors at the perfect distance from its reflective optics to focus X-rays. NuSTAR recently celebrated 10 years since its launch in 2012.

Our eleventh astronomical gift is … eleven days of observations

How long did our Hubble Space Telescope stare at a seemingly empty patch of sky to discover it was full of thousands of faint galaxies? More than 11 days of observations came together to capture this amazing image — that’s about 1 million seconds spread over 400 orbits around Earth!

Our twelfth astronomical gift is … a twelve-kilometer radius

Pulsars are collapsed stellar cores that pack the mass of our Sun into a whirling city-sized ball, compressing matter to its limits. Our NICER telescope aboard the International Space Station helped us precisely measure one called J0030 and found it had a radius of about twelve kilometers — roughly the size of Chicago! This discovery has expanded our understanding of pulsars with the most precise and reliable size measurements of any to date.

Stay tuned to NASA Universe on Twitter and Facebook to keep up with what’s going on in the cosmos every day. You can learn more about the universe here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Cosmic Alphabet Soup: Classifying Stars

If you’ve spent much time stargazing, you may have noticed that while most stars look white, some are reddish or bluish. Their colors are more than just pretty – they tell us how hot the stars are. Studying their light in greater detail can tell us even more about what they’re like, including whether they have planets. Two women, Williamina Fleming and Annie Jump Cannon, created the system for classifying stars that we use today, and we’re building on their work to map out the universe.

By splitting starlight into spectra – detailed color patterns that often feature lots of dark lines – using a prism, astronomers can figure out a star’s temperature, how long it will burn, how massive it is, and even how big its habitable zone is. Our Sun’s spectrum looks like this:

Astronomers use spectra to categorize stars. Starting at the hottest and most massive, the star classes are O, B, A, F, G (like our Sun), K, M. Sounds like cosmic alphabet soup! But the letters aren’t just random – they largely stem from the work of two famous female astronomers.

Williamina Fleming, who worked as one of the famous “human computers” at the Harvard College Observatory starting in 1879, came up with a way to classify stars into 17 different types (categorized alphabetically A-Q) based on how strong the dark lines in their spectra were. She eventually classified more than 10,000 stars and discovered hundreds of cosmic objects!

That was back before they knew what caused the dark lines in spectra. Soon astronomers discovered that they’re linked to a star’s temperature. Using this newfound knowledge, Annie Jump Cannon – one of Fleming’s protégés – rearranged and simplified stellar classification to include just seven categories (O, B, A, F, G, K, M), ordered from highest to lowest temperature. She also classified more than 350,000 stars!

Type O stars are both the hottest and most massive in the new classification system. These giants can be a thousand times bigger than the Sun! Their lifespans are also around 1,000 times shorter than our Sun’s. They burn through their fuel so fast that they only live for around 10 million years. That’s part of the reason they only make up a tiny fraction of all the stars in the galaxy – they don’t stick around for very long.

As we move down the list from O to M, stars become progressively smaller, cooler, redder, and more common. Their habitable zones also shrink because the stars aren’t putting out as much energy. The plus side is that the tiniest stars can live for a really long time – around 100 billion years – because they burn through their fuel so slowly.

Astronomers can also learn about exoplanets – worlds that orbit other stars – by studying starlight. When a planet crosses in front of its host star, different kinds of molecules in the planet’s atmosphere absorb certain wavelengths of light.

By spreading the star’s light into a spectrum, astronomers can see which wavelengths have been absorbed to determine the exoplanet atmosphere’s chemical makeup. Our James Webb Space Telescope will use this method to try to find and study atmospheres around Earth-sized exoplanets – something that has never been done before.

Our upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will study the spectra from entire galaxies to build a 3D map of the cosmos. As light travels through our expanding universe, it stretches and its spectral lines shift toward longer, redder wavelengths. The longer light travels before reaching us, the redder it becomes. Roman will be able to see so far back that we could glimpse some of the first stars and galaxies that ever formed.

Learn more about how Roman will study the cosmos in our other posts:

Roman’s Family Portrait of Millions of Galaxies

New Rose-Colored Glasses for Roman

How Gravity Warps Light

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Visual 'Autocorrect' for NASA Space Telescope

Telescopes located both on the ground and in space continue to dazzle us with incredible images of the universe. We owe these sharp vistas to a series of brilliant astronomers, including Andrea Ghez – an astrophysicist and professor at UCLA – and the “Mother of Hubble,” Nancy Grace Roman.

Did you know that stars don’t actually twinkle? They only look like they do because their light has to travel through our turbulent atmosphere to reach our eyes. As the atmosphere shifts and swirls around, the light from distant stars is slightly refracted, or bent, in different directions. Sometimes it’s directed right at us, but sometimes it’s directed a bit to the side.

It's like someone’s shining a flashlight toward you but moving it around slightly. Sometimes the beam is pointed right at you and appears very bright, and sometimes it's pointed a bit to either side of you and it appears dimmer. The amount of light isn't really changing, but it looks like it is.

This effect creates a problem for ground-based telescopes. Instead of seeing sharp images, astronomers get fuzzy pictures. Special tech known as adaptive optics helps resolve pictures of space so astronomers can see things more clearly. It’s even useful for telescopes that are in space, above Earth’s atmosphere, because tiny imperfections in their optics can blur images, too.

In 2020, Andrea Ghez was awarded a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics for devising an experiment that proved there’s a supermassive black hole embedded in the heart of our galaxy – something Hubble has shown is true of almost every galaxy in the universe! She used the W. M. Keck Observatory’s adaptive optics to track stars orbiting the unseen black hole.

A woman named Nancy Grace Roman, who was NASA’s first chief astronomer, paved the way for telescopes that study the universe from space. An upcoming observatory named in her honor, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, will use a special kind of adaptive optics in its Coronagraph Instrument, which is a technology demonstration designed to block the glare from host stars and reveal dimmer orbiting planets.

Roman’s Coronagraph Instrument will come equipped with deformable mirrors that will serve as a form of visual "autocorrect" by measuring and subtracting starlight in real time. The mirrors will bend and flex to help counteract effects like temperature changes, which can slightly alter the shape of the optics.

Other telescopes have taken pictures of enormous, young, bright planets orbiting far away from their host stars because they’re usually the easiest ones to see. Taking tech that’s worked well on ground-based telescopes to space will help Roman photograph dimmer, older, colder planets than any other observatory has been able to so far. The mission could even snap the first real photograph of a planet like Jupiter orbiting a Sun-like star!

Find out more about the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope on Twitter and Facebook, and learn about the person from which the mission draws its name.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Photographing Planets with the Roman Space Telescope

Nearly 100 years ago, astronomer Bernard Lyot invented the coronagraph – a device that made it possible to recreate a total solar eclipse by blocking the Sun’s light. That helped scientists study the Sun’s corona, which is the outermost part of our star’s atmosphere that’s usually hidden by bright light from its surface.

Our Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, now under construction, will test out a much more advanced version of the same thing. Roman’s Coronagraph Instrument will use special masks to block the glare from host stars but allow the light from dimmer, orbiting planets to filter through. It will also have self-flexing mirrors that will measure and subtract starlight automatically.

This glare-blocking prowess is important because planets can be billions of times dimmer than their host stars! Roman’s high-tech shades will help us take pictures of planets we wouldn’t be able to photograph using any other current telescopes.

Other observatories mainly use this planet-hunting method, called direct imaging, from the ground to photograph huge, bright planets called “super-Jupiters” in infrared light. These worlds can be dozens of times more massive than Jupiter, and they’re so young that they glow brightly thanks to heat left over from their formation. That glow makes them detectable in infrared light.

Roman will take advanced planet-imaging tech to space to get even higher-quality pictures. And while it’s known for being an infrared telescope, Roman will actually photograph planets in visible light, like our eyes can see. That means it will be able to see smaller, older, colder worlds orbiting close to their host stars. Roman could even snap the first-ever image of a planet like Jupiter orbiting a star like our Sun.

Astronomers would ultimately like to take pictures of planets like Earth as part of the search for potentially habitable worlds. Roman’s direct imaging efforts will move us a giant leap in that direction!

And direct imaging is just one component of Roman’s planet-hunting plans. The mission will also use a light-bending method called microlensing to find other worlds, including rogue planets that wander the galaxy untethered to any stars. Scientists also expect Roman to discover 100,000 planets as they cross in front of their host stars!

Find out more about the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope on Twitter and Facebook, and about the person from which the mission draws its name.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

How will the James Webb Space Telescope change how we see the universe? Ask an expert!

The James Webb Space Telescope is launching on December 22, 2021. Webb’s revolutionary technology will explore every phase of cosmic history—from within our solar system to the most distant observable galaxies in the early universe, to everything in between. Postdoctoral Research Associate Naomi Rowe-Gurney will be taking your questions about Webb and Webb science in an Answer Time session on Tuesday, December 14 from noon to 1 p.m EST here on our Tumblr!

🚨 Ask your questions now by visiting http://nasa.tumblr.com/ask.

Dr. Naomi Rowe-Gurney recently completed her PhD at the University of Leicester and is now working at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center as a postdoc through Howard University. As a planetary scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, she’s an expert on the atmospheres of the ice giants in our solar system — Uranus and Neptune — and how the Webb telescope will be able to learn more about them.

The James Webb Space Telescope – fun facts:

Webb is so big it has to fold origami-style to fit into its rocket and will unfold like a “Transformer” in space.

Webb is about 100 times more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope and designed to see the infrared, a region Hubble can only peek at.

With unprecedented sensitivity, it will peer back in time over 13.5 billion years to see the first galaxies born after the Big Bang––a part of space we’ve never seen.

It will study galaxies near and far, young and old, to understand how they evolve.

Webb will explore distant worlds and study the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars, known as exoplanets, searching for chemical fingerprints of possible habitability.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

NASA’s Search for Life: Astrobiology in the Solar System and Beyond

Are we alone in the universe? So far, the only life we know of is right here on Earth. But here at NASA, we’re looking.

We’re exploring the solar system and beyond to help us answer fundamental questions about life beyond our home planet. From studying the habitability of Mars, probing promising “oceans worlds,” such as Titan and Europa, to identifying Earth-size planets around distant stars, our science missions are working together with a goal to find unmistakable signs of life beyond Earth (a field of science called astrobiology).

Dive into the past, present, and future of our search for life in the universe.

Mission Name: The Viking Project

Launch: Viking 1 on August 20, 1975 & Viking 2 on September 9, 1975

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: The Viking Project was our first attempt to search for life on another planet. The mission’s biology experiments revealed unexpected chemical activity in the Martian soil, but provided no clear evidence for the presence of living microorganisms near the landing sites.

Mission Name: Galileo

Launch: October 18, 1989

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: Galileo orbited Jupiter for almost eight years, and made close passes by all its major moons. The spacecraft returned data that continues to shape astrobiology science –– particularly the discovery that Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has evidence of a subsurface ocean with more water than the total amount of liquid water found on Earth.

Mission Name: Kepler and K2

Launch: March 7, 2009

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: Our first planet-hunting mission, the Kepler Space Telescope, paved the way for our search for life in the solar system and beyond. Kepler left a legacy of more than 2,600 exoplanet discoveries, many of which could be promising places for life.

Mission Name: Perseverance Mars Rover

Launch: July 30, 2020

Status: Present

Role in the search for life: Our newest robot astrobiologist is kicking off a new era of exploration on the Red Planet. The rover will search for signs of ancient microbial life, advancing the agency’s quest to explore the past habitability of Mars.

Mission Name: James Webb Space Telescope

Launch: 2021

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Webb will be the premier space-based observatory of the next decade. Webb observations will be used to study every phase in the history of the universe, including planets and moons in our solar system, and the formation of distant solar systems potentially capable of supporting life on Earth-like exoplanets.

Mission Name: Europa Clipper

Launch: Targeting 2024

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Europa Clipper will investigate whether Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, with its subsurface ocean, has the capability to support life. Understanding Europa’s habitability will help scientists better understand how life developed on Earth and the potential for finding life beyond our planet.

Mission Name: Dragonfly

Launch: 2027

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Dragonfly will deliver a rotorcraft to visit Saturn’s largest and richly organic moon, Titan. This revolutionary mission will explore diverse locations to look for prebiotic chemical processes common on both Titan and Earth.

For more on NASA’s search for life, follow NASA Astrobiology on Twitter, on Facebook, or on the web.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

The Stellar Buddy System

Our Sun has an entourage of planets, moons, and smaller objects to keep it company as it traverses the galaxy. But it’s still lonely compared to many of the other stars out there, which often come in pairs. These cosmic couples, called binary stars, are very important in astronomy because they can easily reveal things that are much harder to learn from stars that are on their own. And some of them could even host habitable planets!

The birth of a stellar duo

New stars emerge from swirling clouds of gas and dust that are peppered throughout the galaxy. Scientists still aren’t sure about all the details, but turbulence deep within these clouds may give rise to knots that are denser than their surroundings. The knots have stronger gravity, so they can pull in more material and the cloud may begin to collapse.

The material at the center heats up. Known as a protostar, it is this hot core that will one day become a star. Sometimes these spinning clouds of collapsing gas and dust may break up into two, three, or even more blobs that eventually become stars. That would explain why the majority of the stars in the Milky Way are born with at least one sibling.

Seeing stars

We can’t always tell if we’re looking at binary stars using just our eyes. They’re often so close together in the sky that we see them as a single star. For example, Sirius, the brightest star we can see at night, is actually a binary system (see if you can spot both stars in the photo above). But no one knew that until the 1800s.

Precise observations showed that Sirius was swaying back and forth like it was at a middle school dance. In 1862, astronomer Alvan Graham Clark used a telescope to see that Sirius is actually two stars that orbit each other.

But even through our most powerful telescopes, some binary systems still masquerade as a single star. Fortunately there are a couple of tricks we can use to spot these pairs too.

Since binary stars orbit each other, there’s a chance that we’ll see some stars moving toward and away from us as they go around each other. We just need to have an edge-on view of their orbits. Astronomers can detect this movement because it changes the color of the star’s light – a phenomenon known as the Doppler effect.

Stars we can find this way are called spectroscopic binaries because we have to look at their spectra, which are basically charts or graphs that show the intensity of light being emitted over a range of energies. We can spot these star pairs because light travels in waves. When a star moves toward us, the waves of its light arrive closer together, which makes its light bluer. When a star moves away, the waves are lengthened, reddening its light.

Sometimes we can see binary stars when one of the stars moves in front of the other. Astronomers find these systems, called eclipsing binaries, by measuring the amount of light coming from stars over time. We receive less light than usual when the stars pass in front of each other, because the one in front will block some of the farther star’s light.

Sibling rivalry

Twin stars don’t always get along with each other – their relationship may be explosive! Type Ia supernovae happen in some binary systems in which a white dwarf – the small, hot core left over when a Sun-like star runs out of fuel and ejects its outer layers – is stealing material away from its companion star. This results in a runaway reaction that ultimately detonates the thieving star. The same type of explosion may also happen when two white dwarfs spiral toward each other and collide. Yikes!

Scientists know how to determine how bright these explosions should truly be at their peak, making Type Ia supernovae so-called standard candles. That means astronomers can determine how far away they are by seeing how bright they look from Earth. The farther they are, the dimmer they appear. Astronomers can also look at the wavelengths of light coming from the supernovae to find out how fast the dying stars are moving away from us.

Studying these supernovae led to the discovery that the expansion of the universe is speeding up. Our Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will scan the skies for these exploding stars when it launches in the mid-2020s to help us figure out what’s causing the expansion to accelerate – a mystery known as dark energy.

Spilling stellar secrets

Astronomers like finding binary systems because it’s a lot easier to learn more about stars that are in pairs than ones that are on their own. That’s because the stars affect each other in ways we can measure. For example, by paying attention to how the stars orbit each other, we can determine how massive they are. Since heavier stars burn hotter and use up their fuel more quickly than lighter ones, knowing a star’s mass reveals other interesting things too.

By studying how the light changes in eclipsing binaries when the stars cross in front of each other, we can learn even more! We can figure out their sizes, masses, how fast they’re each spinning, how hot they are, and even how far away they are. All of that helps us understand more about the universe.

Tatooine worlds

Thanks to observatories such as our Kepler Space Telescope, we know that worlds like Luke Skywalker’s home planet Tatooine in “Star Wars” exist in real life. And if a planet orbits at the right distance from the two stars, it could even be habitable (and stay that way for a long time).

In 2019, our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) found a planet, known as TOI-1338 b, orbiting a pair of stars. These worlds are tricker to find than planets with only one host star, but TESS is expected to find several more!

Want to learn more about the relationships between stellar couples? Check out this Tumblr post: https://nasa.tumblr.com/post/190824389279/cosmic-couples-and-devastating-breakups

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Three NASA Telescopes Look at an Angry Young Star Together

Science is a shared endeavor. We learn more when we work together. Today, July 18, we’re using three different space telescopes to observe the same star/planet system!

As our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) enters its third year of observations, it's taking a new look at a familiar system this month. And today it won't be alone. Astronomers are looking at AU Microscopii, a young fiery nearby star – about 22 million years old – with the TESS, NICER and Swift observatories.

TESS will be looking for more transits – the passage of a planet across a star – of a recently-discovered exoplanet lurking in the dust of AU Microscopii (called AU Mic for short). Astronomers think there may be other worlds in this active system, as well!

Our Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) telescope on the International Space Station will also focus on AU Mic today. While NICER is designed to study neutron stars, the collapsed remains of massive stars that exploded as supernovae, it can study other X-ray sources, too. Scientists hope to observe stellar flares by looking at the star with its high-precision X-ray instrument.

Scientists aren't sure where the X-rays are coming from on AU Mic — it could be from a stellar corona or magnetic hot spots. If it's from hot spots, NICER might not see the planet transit, unless it happens to pass over one of those spots, then it could see a big dip!

A different team of astronomers will use our Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory to peer at AU Mic in X-ray and UV to monitor for high-energy flares while TESS simultaneously observes the transiting planet in the visible spectrum. Stellar flares like those of AU Mic can bathe planets in radiation.

Studying high-energy flares from AU Mic with Swift will help us understand the flare-rate over time, which will help with models of the planet’s atmosphere and the system’s space weather. There's even a (very) small chance for Swift to see a hint of the planet's transit!

The flares that a star produces can have a direct impact on orbiting planets' atmospheres. The high-energy photons and particles associated with flares can alter the chemical makeup of a planet's atmosphere and erode it away over time.

Another time TESS teamed up with a different spacecraft, it discovered a hidden exoplanet, a planet beyond our solar system called AU Mic b, with the now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope. That notable discovery inspired our latest poster! It’s free to download in English and Spanish.

Spitzer’s infrared instrument was ideal for peering at dusty systems! Astronomers are still using data from Spitzer to make discoveries. In fact, the James Webb Space Telescope will carry on similar study and observe AU Mic after it launches next year.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Are We Alone? How NASA Is Trying to Answer This Question.

One of the greatest mysteries that life on Earth holds is, “Are we alone?”

At NASA, we are working hard to answer this question. We’re scouring the universe, hunting down planets that could potentially support life. Thanks to ground-based and space-based telescopes, including Kepler and TESS, we’ve found more than 4,000 planets outside our solar system, which are called exoplanets. Our search for new planets is ongoing — but we’re also trying to identify which of the 4,000 already discovered could be habitable.

Unfortunately, we can’t see any of these planets up close. The closest exoplanet to our solar system orbits the closest star to Earth, Proxima Centauri, which is just over 4 light years away. With today’s technology, it would take a spacecraft 75,000 years to reach this planet, known as Proxima Centauri b.

How do we investigate a planet that we can’t see in detail and can’t get to? How do we figure out if it could support life?

This is where computer models come into play. First we take the information that we DO know about a far-off planet: its size, mass and distance from its star. Scientists can infer these things by watching the light from a star dip as a planet crosses in front of it, or by measuring the gravitational tugging on a star as a planet circles it.

We put these scant physical details into equations that comprise up to a million lines of computer code. The code instructs our Discover supercomputer to use our rules of nature to simulate global climate systems. Discover is made of thousands of computers packed in racks the size of vending machines that hum in a deafening chorus of data crunching. Day and night, they spit out 7 quadrillion calculations per second — and from those calculations, we paint a picture of an alien world.

While modeling work can’t tell us if any exoplanet is habitable or not, it can tell us whether a planet is in the range of candidates to follow up with more intensive observations.

One major goal of simulating climates is to identify the most promising planets to turn to with future technology, like the James Webb Space Telescope, so that scientists can use limited and expensive telescope time most efficiently.

Additionally, these simulations are helping scientists create a catalog of potential chemical signatures that they might detect in the atmospheres of distant worlds. Having such a database to draw from will help them quickly determine the type of planet they’re looking at and decide whether to keep observing or turn their telescopes elsewhere.

Learn more about exoplanet exploration, here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

How Do We Learn About a Planet’s Atmosphere?

The first confirmation of a planet orbiting a star outside our solar system happened in 1995. We now know that these worlds – also known as exoplanets – are abundant. So far, we’ve confirmed more than 4000. Even though these planets are far, far away, we can still study them using ground-based and space-based telescopes.

Our upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will study the atmospheres of the worlds in our solar system and those of exoplanets far beyond. Could any of these places support life? What Webb finds out about the chemical elements in these exoplanet atmospheres might help us learn the answer.

How do we know what’s in the atmosphere of an exoplanet?

Most known exoplanets have been discovered because they partially block the light of their suns. This celestial photo-bombing is called a transit.

During a transit, some of the star's light travels through the planet's atmosphere and gets absorbed.

The light that survives carries information about the planet across light-years of space, where it reaches our telescopes.

(However, the planet is VERY small relative to the star, and VERY far away, so it is still very difficult to detect, which is why we need a BIG telescope to be sure to capture this tiny bit of light.)

So how do we use a telescope to read light?

Stars emit light at many wavelengths. Like a prism making a rainbow, we can separate light into its separate wavelengths. This is called a spectrum. Learn more about how telescopes break down light here.

Visible light appears to our eyes as the colors of the rainbow, but beyond visible light there are many wavelengths we cannot see.

Now back to the transiting planet...

As light is traveling through the planet's atmosphere, some wavelengths get absorbed.

Which wavelengths get absorbed depends on which molecules are in the planet's atmosphere. For example, carbon monoxide molecules will capture different wavelengths than water vapor molecules.

So, when we look at that planet in front of the star, some of the wavelengths of the starlight will be missing, depending on which molecules are in the atmosphere of the planet.

Learning about the atmospheres of other worlds is how we identify those that could potentially support life...

...bringing us another step closer to answering one of humanity's oldest questions: Are we alone?

Watch the full video where this method of hunting for distant planets is explained:

To learn more about NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, visit the website, or follow the mission on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Text and graphics credit Space Telescope Science Institute

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

TESS’s first-year of planet-hunting was out of this world

Have you ever looked up at the night sky and wondered ... what other kinds of planets are out there? Our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) just spent its first year bringing us a step closer to exploring the planets around the nearest and brightest stars in the southern sky and is now doing the same in the north.

TESS has been looking for dips in the brightness of stars that could be a sign of something we call “transits.” A transit happens when a planet passes between its star and us. It’s like when a bug flies in front of a light bulb. You may not notice the tiny drop in brightness when the bug blocks some of the light from reaching your eyes, but a sensitive camera could. The cameras on TESS are designed to detect those tiny drops in starlight caused by a transiting planet many light-years away.

In the last year TESS has found 24 planets and more than 900 new candidate planets. And TESS is only halfway through its goal of mapping over three-fourths of our skies, which means there’s plenty more to discover!

TESS has been looking for planets around the closest, brightest stars because they will be the best planets to explore more thoroughly with future missions. We can even see a few of these stars with our own eyes, which means we’ve been looking at these planets for millions of years and didn’t even know it.

We spent thousands of years staring at our closest neighbor, the Moon, and asking questions: What is it like? Could we live there? What is it made of (perhaps cheese?). Of course, now we can travel to the Moon and explore it ourselves (turns out, not made of cheese).

But for the worlds TESS is discovering, the commute to answer those questions would be killer. It took 35 years for Voyager 1 to cross into interstellar space (the region between stars), and it’s zipping along at over 38,000 mph! At that rate it would take more than a half-a-million years to reach the nearest stars and planets that TESS is discovering.

While exploring these distant worlds in person isn’t an option, we have other ways of learning what they are like. TESS can tell us where a planet is, its size and its overall temperature, but observatories on the ground and in space like our upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will be able to learn even more — like whether or not a planet has an atmosphere and what it’s made of.

Here are a few of the worlds that our planet hunter discovered in the last year.

Earth-Sized Planet

The first Earth-sized planet discovered by TESS is about 90% the size of our home planet and orbits a star 53 light-years away. The planet is called HD 21749 c (what a mouthful!) and is actually the second planet TESS has discovered orbiting that star, which you can see in the southern constellation Reticulum.

The planet may be Earth-sized, but it would not be a pleasant place to live. It’s very close to its star and could have a surface temperature of 800 degrees Fahrenheit, which would be like sitting inside a commercial pizza oven.

Water World?

The other planet discovered in that star system, HD 21749 b, is about three times Earth’s size and orbits the star every 36 days. It has the longest orbit of any planet within 100 light-years of our solar system detected with TESS so far.

The planet is denser than Neptune, but isn’t made of rock. Scientists think it might be a water planet or have a totally new type of atmosphere. But because the planet isn’t ideal for follow-up study, for now we can only theorize what the planet is actually like. Could it be made of pudding? Maybe … but probably not.

Magma World

One of the first planets TESS discovered, called LHS 3844 b, is roughly Earth’s size, but is so close to its star that it orbits in just 11 hours. For reference, Mercury, which is more than two and a half times closer to the Sun than we are, completes an orbit in just under three months.

Because the planet is so close to its star, the day side of the planet might get so hot that pools and oceans of magma form on its rocky surface, which would make for a rather unpleasant day at the beach.

TESS’s Smallest Planet

The smallest planet TESS has discovered, called L 98-59 b, is between the size of Earth and Mars and orbits its star in a little over two days. Its star also hosts two other TESS-discovered worlds.

Because the planet lies so close to its star, it gets 22 times the radiation we get here on Earth. Yikes! It is also not located in its star’s habitable zone, which means there probably isn’t any liquid water on the surface. Those two factors make it an unlikely place to find life, but scientists believe it will be a good candidate for follow-up studies by other telescopes.

Other Data

While TESS’s team is hunting for planets around close, bright stars, it’s also collecting information on all sorts of other things. From transits around dimmer, farther stars to other objects in our solar system and events outside our galaxy, data from TESS can help astronomers learn a lot more about the universe. Comets and black holes and supernovae, oh my!

Interested in joining the hunt? TESS’s data are released online, so citizen scientists around the world can help us discover new worlds and better understand our universe.

Stay tuned for TESS’s next year of science as it monitors the stars that more than 6.5 billion of us in the northern hemisphere see every night.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

6 Things You Didn’t Know About Our ‘First’ Space Flight Center

When NASA began operations on Oct. 1, 1958, we consisted mainly of the four laboratories of our predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). Hot on the heels of NASA’s first day of business, we opened the Goddard Space Flight Center. Chartered May 1, 1959, and located in Greenbelt, Maryland, Goddard is home to one of the largest groups of scientists and engineers in the world. These people are building, testing and experimenting their way toward answering some of the universe’s most intriguing questions.

To celebrate 60 years of exploring, here are six ways Goddard shoots for the stars.

For the last 60 years, we’ve kept a close eye on our home planet, watching its atmosphere, lands and ocean.

Goddard instruments were crucial in tracking the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica as it grew and eventually began to show signs of healing. Satellites and field campaigns track the changing height and extent of ice around the globe. Precipitation missions give us a global, near-real-time look at rain and snow everywhere on Earth. Researchers keep a record of the planet’s temperature, and Goddard supercomputer models consider how Earth will change with rising temperatures. From satellites in Earth’s orbit to field campaigns in the air and on the ground, Goddard is helping us understand our planet.

We seek to answer the big questions about our universe: Are we alone? How does the universe work? How did we get here?

We’re piecing together the story of our cosmos, from now all the way back to its start 13.7 billion years ago. Goddard missions have contributed to our understanding of the big bang and have shown us nurseries where stars are born and what happens when galaxies collide. Our ongoing census of planets far beyond our own solar system (several thousand known and counting!) is helping us hone in on which ones might be potentially habitable.

We study our dynamic Sun.

Our Sun is an active star, with occasional storms and a constant outflow of particles, radiation and magnetic fields that fill the solar system out far past the orbit of Neptune. Goddard scientists study the Sun and its activity with a host of satellites to understand how our star affects Earth, planets throughout the solar system and the nature of the very space our astronauts travel through.

We explore the planets, moons and small objects in the solar system and beyond.

Goddard instruments (well over 100 in total!) have visited every planet in the solar system and continue on to new frontiers. What we’ve learned about the history of our solar system helps us piece together the mysteries of life: How did life in our solar system form and evolve? Can we find life elsewhere?

Over 60 years, our communications networks have enabled hundreds of NASA spacecraft to “phone home.”

Today, Goddard communications networks bring down 98 percent of our spacecraft data – nearly 30 terabytes per day! This includes not only science data, but also key information related to spacecraft operations and astronaut health. Goddard is also leading the way in creating cutting-edge solutions like laser communications that will enable exploration – faster, better, safer – for generations to come. Pew pew!

Exploring the unknown often means we must create new ways of exploring, new ways of knowing what we’re “seeing.”

Goddard’s technologists and engineers must often invent tools, mechanisms and sensors to return information about our universe that we may not have even known to look for when the center was first commissioned.

Behind every discovery is an amazing team of people, pushing the boundaries of humanity’s knowledge. Here’s to the ones who ask questions, find answers and ask questions some more!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

One Year Into Our Planet-Hunting TESS Mission

Our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), launched last year on April 18, is completing a year in space, surveying the skies to find the closest, most exciting planets outside our solar system for further study. Worlds that TESS is hunting for include super-Earths, rocky planets, gas giants, and maybe even some Earth-sized planets — and much, much more! TESS is scanning the whole sky one section at a time, monitoring the brightness of stars for periodic dips caused by planets transiting (that is, passing in front of) those stars. So far, TESS has found 548 candidates and 10 confirmed exoplanets.

Since its launch, TESS has orbited Earth a total of 28 times. TESS has a unique elliptical orbit that circuits around Earth twice every time the Moon orbits. This allows TESS’s cameras to monitor each patch of sky continuously for nearly a month at a time. To get into this special orbit, TESS made a series of loops culminating in a lunar gravitational assist, which gave it the final push it needed.

Did you know that TESS has some serious mileage? The spacecraft has traveled about 20 million miles so far, which works out to an average of about 2,200 miles per hour. That’s faster than any roadrunner we’ve ever seen! This would be four times faster than an average jet. You’d get to your destination in no time!

TESS downloads data during its closest approach to Earth about every two weeks. So far, it has returned 12,000 gigabytes of data. That’s as if you streamed about 3,000 movies on Netflix. Get the popcorn ready! If you total all the pixels from every image taken using all four of the TESS cameras — which is about 600 full-frame images per orbit, you’d get about 805 billion pixels. This is like half a million iPhone screens put together!

When the Kepler Space Telescope reached the end of its mission, it passed the planet-finding torch to TESS. Where Kepler's view was deep — looking for planets as far away as 3,000 light-years — TESS's view is wide, surveying nearly the entire sky over two years. Each sector TESS views is 20 times larger than Kepler's field of view.

TESS will continue to survey the sky and is expected to find about 20,000 exoplanets in the two years it'll take to complete a scan of nearly the entire sky. Before TESS, several thousand candidate exoplanets were found, and more than 3,000 of these were confirmed. Some of these exoplanets are expected to range from small, rocky worlds to giant planets, showcasing the diversity of planets in the galaxy.

The TESS mission is led by MIT and came together with the help of many different partners. You can keep up with the latest from the TESS mission by following mission updates and keep track of the number of candidates and confirmed exoplanets.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

How Big is Our Galaxy, the Milky Way?

When we talk about the enormity of the cosmos, it’s easy to toss out big numbers – but far harder to wrap our minds around just how large, how far and how numerous celestial bodies like exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – really are.

So. How big is our Milky Way Galaxy?

We use light-time to measure the vast distances of space.

It’s the distance that light travels in a specific period of time. Also: LIGHT IS FAST, nothing travels faster than light.

How far can light travel in one second? 186,000 miles. It might look even faster in metric: 300,000 kilometers in one second. See? FAST.

How far can light travel in one minute? 11,160,000 miles. We’re moving now! Light could go around the Earth a bit more than 448 times in one minute.

Speaking of Earth, how long does it take light from the Sun to reach our planet? 8.3 minutes. (It takes 43.2 minutes for sunlight to reach Jupiter, about 484 million miles away.) Light is fast, but the distances are VAST.

In an hour, light can travel 671 million miles. We’re still light-years from the nearest exoplanet, by the way. Proxima Centauri b is 4.2 light-years away. So… how far is a light-year? 5.8 TRILLION MILES.

A trip at light speed to the very edge of our solar system – the farthest reaches of the Oort Cloud, a collection of dormant comets way, WAY out there – would take about 1.87 years.

Our galaxy contains 100 to 400 billion stars and is about 100,000 light-years across!

One of the most distant exoplanets known to us in the Milky Way is Kepler-443b. Traveling at light speed, it would take 3,000 years to get there. Or 28 billion years, going 60 mph. So, you know, far.

SPACE IS BIG.

Read more here: go.nasa.gov/2FTyhgH

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

55 Cancri e: Where Skies Sparkle Above a Never-ending Ocean of Lava

We’ve discovered thousands of exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – so far. These worlds are mysterious, but observations from telescopes on the ground and in space help us understand what they might look like.

Take the planet 55 Cancri e, for instance. It’s relatively close, galactically speaking, at 41 light-years away. It’s a rocky planet, nearly two times bigger than Earth, that whips around its star every 18 hours (as opposed to the 365 days it takes our planet to orbit the Sun. Slacker).

The planet’s star, 55 Cancri, is slightly smaller than our Sun, but it’s 65 times closer than the Sun is to Earth. Imagine a massive sun on the horizon! Because 55 Cancri e is so close to its star, it’s tidally locked just like our Moon is to the Earth. One side is always bathed in daylight, the other is in perpetual darkness. It’s also hot. Really hot. So hot that silicate rocks would melt into a molten ocean of melted rock. IT’S COVERED IN AN OCEAN OF LAVA. So, it’s that hot (between 3,140 degrees and 2,420 degrees F).

Scientists think 55 Cancri e also may harbor a thick atmosphere that circulates heat from the dayside to the nightside. Silicate vapor in the atmosphere could condense into sparkling clouds on the cooler, darker nightside that would reflect the lava below. It’s also possible that it would rain sand on the nightside, but … sparkling skies!

Check out our Exoplanet Travel Bureau's latest 360-degree visualization of 55 Cancri e and download the travel poster at https://go.nasa.gov/2HOyfF3.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

NASA’s New Planet Hunter Reveals a Sky Full of Stars

NASA’s newest planet-hunting satellite — the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS for short — has just released its first science image using all of its cameras to capture a huge swath of the sky! TESS is NASA’s next step in the search for planets outside our solar system, called exoplanets.

This spectacular image, the first released using all four of TESS’ cameras, shows the satellite’s full field of view. It captures parts of a dozen constellations, from Capricornus (the Sea Goat) to Pictor (the Painter’s Easel) — though it might be hard to find familiar constellations among all these stars! The image even includes the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, our galaxy’s two largest companion galaxies.

The science community calls this image “first light,” but don’t let that fool you — TESS has been seeing light since it launched in April. A first light image like this is released to show off the first science-quality image taken after a mission starts collecting science data, highlighting a spacecraft’s capabilities.

TESS has been busy since it launched from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. First TESS needed to get into position, which required a push from the Moon. After nearly a month in space, the satellite passed about 5,000 miles from the Moon, whose gravity gave it the boost it needed to get into a special orbit that will keep it stable and maximize its view of the sky.

During those first few weeks, we also got a sneak peek of the sky through one of TESS’s four cameras. This test image captured over 200,000 stars in just two seconds! The spacecraft was pointed toward the constellation Centaurus when it snapped this picture. The bright star Beta Centauri is visible at the lower left edge, and the edge of the Coalsack Nebula is in the right upper corner.

After settling into orbit, scientists ran a number of checks on TESS, including testing its ability to collect a set of stable images over a prolonged period of time. TESS not only proved its ability to perform this task, it also got a surprise! A comet named C/2018 N1 passed through TESS’s cameras for about 17 hours in July.

The images show a treasure trove of cosmic curiosities. There are some stars whose brightness changes over time and asteroids visible as small moving white dots. You can even see an arc of stray light from Mars, which is located outside the image, moving across the screen.

Now that TESS has settled into orbit and has been thoroughly tested, it’s digging into its main mission of finding planets around other stars. How will it spot something as tiny and faint as a planet trillions of miles away? The trick is to look at the star!

So far, most of the exoplanets we’ve found were detected by looking for tiny dips in the brightness of their host stars. These dips are caused by the planet passing between us and its star – an event called a transit. Over its first two years, TESS will stare at 200,000 of the nearest and brightest stars in the sky to look for transits to identify stars with planets.

TESS will be building on the legacy of NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, which also used transits to find exoplanets. TESS’s target stars are about 10 times closer than Kepler’s, so they’ll tend to be brighter. Because they're closer and brighter, TESS’s target stars will be ideal candidates for follow-up studies with current and future observatories.

TESS is challenging over 200,000 of our stellar neighbors to a staring contest! Who knows what new amazing planets we’ll find?

The TESS mission is led by MIT and came together with the help of many different partners. You can keep up with the latest from the TESS mission by following mission updates.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Our Kepler Space Telescope team has identified 219 new planet candidates, 10 of which are near-Earth size and in the habitable zone of their respective stars. The habitable zone is the range of distance from a star where liquid water could pool on the surface of a rocky planet to possibly sustain life. This artist rendering is of one of the thousands of planets detected by Kepler beyond our solar system. These exoplanets, as they’re called, vary widely in size and orbital distances, showing us that most stars are home to at least one planet. Learn more.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

It’s May the 4th: Are Star Wars Planets Real?

Look at what we’ve found so far.

Is your favorite Star Wars planet a desert world or an ice planet or a jungle moon?

It’s possible that your favorite planet exists right here in our galaxy. Astronomers have found over 3,700 planets around other stars, called “exoplanets.”

Some of these alien worlds could be very similar to arid Tatooine, watery Scarif and even frozen Hoth, according to our scientists.

Find out if your planet exists in a galaxy far, far away or all around you. And May the Fourth be with you!

Planets With Two Suns

From Luke Skywalker’s home world Tatooine, you can stand in the orange glow of a double sunset. The same could said for Kepler-16b, a cold gas giant roughly the size of Saturn, that orbits two stars. Kepler-16b was the Kepler telescope’s first discovery of a planet in a “circumbinary” orbit (that is, circling both stars, as opposed to just one, in a double star system).

The best part is that Tatooine aka Kepler-16b was just the first. It has family. A LOT of family. Half the stars in our galaxy are pairs, rather than single stars like our sun. If every star has at least one planet, that’s billions of worlds with two suns. Billions! Maybe waiting for life to be found on them.

Desert Worlds

Mars is a cold desert planet in our solar system, and we have plenty of examples of scorching hot planets in our galaxy (like Kepler-10b), which orbits its star in less than a day)! Scientists think that if there are other habitable planets in the galaxy, they’re more likely to be desert planets than ocean worlds. That’s because ocean worlds freeze when they’re too far from their star, or boil off their water if they’re too close, potentially making them unlivable. Perhaps, it’s not so weird that both Luke Skywalker and Rey grew up on planets that look a lot alike.

Ice Planets

An icy super-Earth named OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb reminded scientists so much of the frozen Rebel base they nicknamed it “Hoth,” after its frozen temperature of minus 364 degrees Fahrenheit. Another Hoth-like planet was discovered in April 2017; an Earth-mass icy world orbiting its star at the same distance as Earth orbits the sun. But its star is so faint, the surface of OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb is probably colder than Pluto.

Forest worlds

Both the forest moon of Endor and Takodana, the home of Han Solo’s favorite cantina in “Force Awakens,” are green like our home planet. But astrobiologists think that plant life on other worlds could be red, black, or even rainbow-colored!

In February 2017, the Spitzer Space Telescope discovered seven Earth-sized planets in the same system, orbiting the tiny red star TRAPPIST-1.

The light from a red star, also known as an M dwarf, is dim and mostly in the infrared spectrum (as opposed to the visible spectrum we see with our sun). And that could mean plants with wildly different colors than what we’re used to seeing on Earth. Or, it could mean animals that see in the near-infrared.

What About Moons?